Ian D. Fowler FBHI

Uhrenrestaurator u. Uhrenhistoriker

Uhrmacher Biographien

Charles Shepherd Jr. / London

Some short notes about his lifeby Eugen Denkel

Charles Shepherd Jr. was born in 1829. He was the son of a chronometer maker also by the first name of Charles and had a sister and three brothers. Two of his brothers also worked as chronometer makers.

1829

Charles Shepherd Jr. was born on 20 September in Pentonville (parish of Clerkenwell).

1841

Shepherd Chas. chronomet. ma. 7 Chadwell st. St. John st. rd (Post Office London Directory, 1841. Part 1: Street, Commercial, & Trades Directories) (the house still exists).

1845

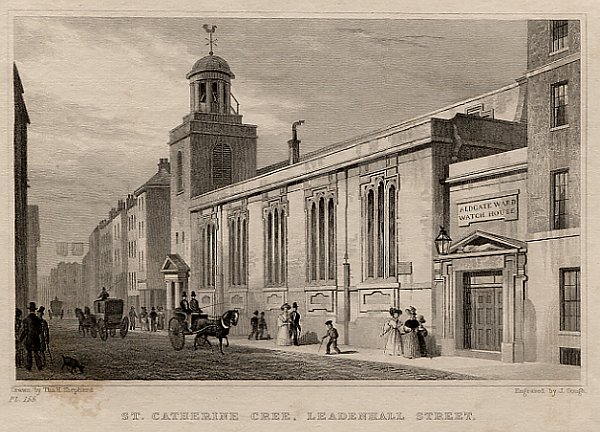

Francis John Shepherd (second brother of Charles Shepherd Jr.) was born on 4 January. Date of christening: 29 March 1845 in St Katherine Cree, London. The family then moved to Leadenhall Street before 1845. Francis John later worked as a merchant clerk and died in 1874.

53 Leadenhall street

Source: Newly drawn after a template from "Tallis London Street View's"

1849

Charles Shepherd Jr. was granted patent No. 12567 “Improvements in Working clocks and other timekeepers, Telegraphs and Machinery by Electricity”.

1849

Charles Shepherd Jr. installed a master clock with eight slave clocks in Pawson's Warehouse, St Paul's Churchyard, London.

1850

On 16 January, Charles Shepherd Jr. was affiliated to the Royal Society of Arts (Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures & Commerce) (nominated by C. W. Barlow).

1851

Charles Shepherd Jr. published his essay “On the Application of Electro-Magnetism as a Motor for Clocks”.

1851

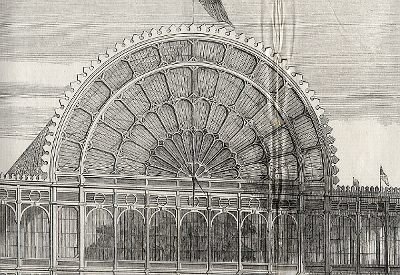

Charles Shepherd Jr. constructed and installed a master clock with slave clocks in the exhibition building of the Great Exhibition, Hyde Park, London. Shepherd attended with an exhibition stand.

Exterior view of Shepherd's clock at Crystal Palace, 1851

Source: The Illustrated London News May 3 1851 / Archive Denkel

1852

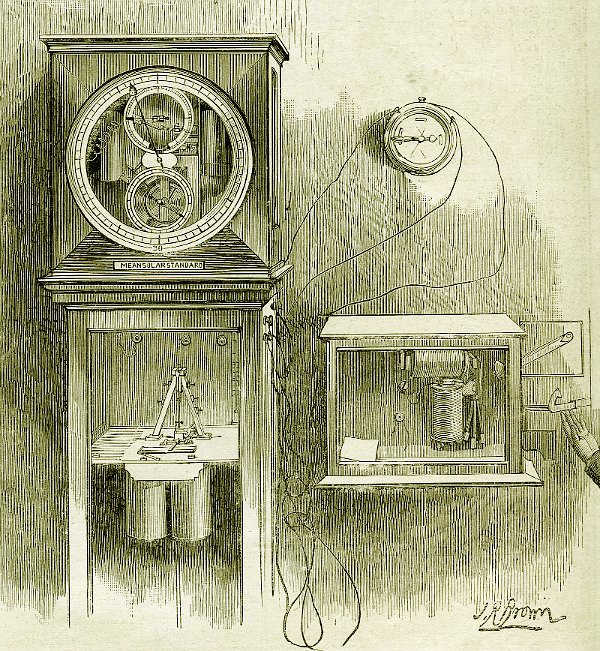

On 4 June, Charles Shepherd Jr. supplied and installed the master clock of the North Dome at the Royal Greenwich Observatory, as commissioned by its director, Astronomer Royal George Biddell Airy, as well as one slave clock for the gate and three slave clocks installed inside the building.

1852

On 2 August, Shepherd’s clock installation at the Greenwich Observatory went into operation. It consisted of the master clock and the slave clocks in the Chronometer Room, the Computing Room and the Dwelling House.

Master clock by Shepherd Royal Observatory Greenwich.

Source: The Graphic, August 8, 1885. / Archiv Denkel.

1852

On 5 August at 4 p.m. time signals were sent from the Greenwich Observatory to London (London Bridge Terminus) for the first time.

1852

On 14 August, the Shepherd Gate Clock at the entrance to the Greenwich Observatory went into operation.

1852

In June the inventor Alexander Bain wrote a

letter to Airy.

He protested against the clock installation by Shepherd and accused him

of infringing his own patents. This letter led to an extensive

correspondence with Bain's lawyer. Airy agreed to remove the

inscription on the Gate Clock (“Shepherd Patentee 53 Leadenhall St

London Galvano Magnetic Clock”) until the rights were clarified. On 3

December Bain went bankrupt. The hearing at Basinghall Street

Bankruptcy Court was then held on 29 April 1853. Bain's creditors were

not interested in proceeding with the patent dispute. So the original

inscription was reinstalled.

1853

On 12 January Charles Shepherd Jr. gave a talk to the Royal Society of Arts titled “On Improvements Electric in Electric Clocks, and the Means of Working the Greenwich Time Signals”.

1853

On 10 June Charles Shepherd Jr. was endowed with the Medal of the Royal Society of Arts for his "Improvements to electric clocks". Prince Albert had the chair during the ceremony. Altogether 33 people were honoured for their merits.

1853

On 12 July Charles Shepherd Jr. married Mary

Osmond just before their

departure to India. The marriage took place in St Katherine Cree,

London. Mary Osmond’s father Robert Osmond was a silk dyer living in 99

Leadenhall Street. Charles Shepherd Jr. and his wife had grown up not

far from each other. It may be possible that they had known each other

from an early age. Perhaps Shepherd married his childhood love after he

had gained social standing and become financially successful.

St. Catherine Cree Church Leadenhall Street.

Source: Drawn by Th. H. Shepherd, Engraved by J. Gough / Archiv Denkel

Opposite, on the other side of the street was the business of Shepherd.

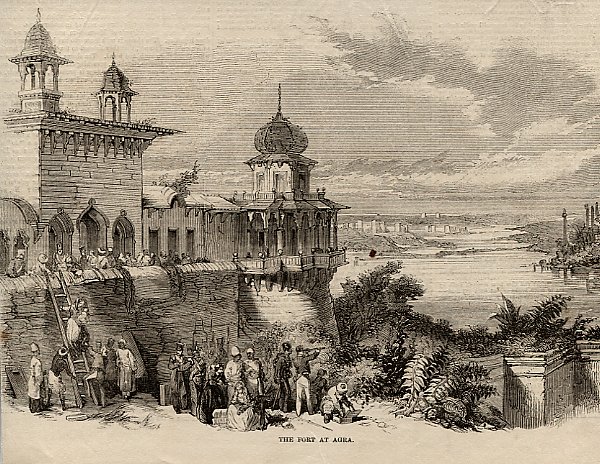

Shepherd delivers four Galvano Magnetic Regulators for the new Electric Telegraph line from Calcutta to Agra.

1853

This year was a turning point in the life of

Charles Shepherd

Jr. He moved to India and started employment as 1st Class Assistant in

the construction of the telegraph line from Kolkata to Agra. Shepherd’s

company supplied electric clocks for the construction of the telegraph

lines in India. William Brooke O'Shaughnessy, Superintendent of

Telegraphs, had been an eyewitness the first time signals had been

transmitted from Greenwich to London Bridge; thus, he had become aware

of Shepherd and eventually made him his assistant in India. But what

was the reason for Shepherd taking up this position and making a long,

exhausting journey to India? Up to that moment Charles Shepherd Jr. had

been successful in London. Why did he now see his future career in

India and not in England? In England, a growing market for electric

clock systems and time distribution had developed. So why did he now

turn his interests to the field of telegraphy? Was it the spirit of

adventure in a young man? Perhaps Shepherd wanted to explore whether

there was an opportunity to set up a branch office of Messrs. Shepherd

& Son in India. But there are also other possible motives why

Shepherd left England, and this may be an evidence that Shepherd had

evaluated his position and his job opportunities in England

realistically. From the clock system of the Great Exhibition we know

that there had been a failure of the large slave clock above the

entrance during the exhibition. It turned out that the cables had been

cut, suggesting sabotage. This is not surprising as the new technology

of electric clock systems eventually threatened all industrial

enterprises and traditional craftsmen: If this new technique prevailed

nationwide, mechanical clocks with many elaborately manufactured items

would no longer be needed. There would no longer be the need for

foundries manufacturing the large parts of tower clocks, skilled

workers in traditional clock-making, clock makers regulating the

clocks, etc. This could only be prevented by demonstrating the

unreliability of electric clocks. Therefore, the sabotage of the clock

at the entrance of the building had been a viable way to prove to

everyone that the new technique was untrustworthy. The failure of the

clock was a welcome opportunity for the horologist Edmund Beckett

Denison (Grimthorpe), who had designed the mechanism for the clock of

the Palace of Westminster, to repeat again that electricity was not in

a position to move large clock hands. Edmund Beckett Denison became the

mouthpiece of the electric clocks opponents. As a lawyer he was

predestined for this task and could at the same time promote his own

mechanical tower clock constructions. In his book, “A rudimentary

treatise on clocks, watches and bells by Grimthorpe”, which was

published in several editions, he crusaded against Shepherd’s electric

clocks.

Regarding Airy and his interests, one can only make assumption. His goal was probably primarily the strengthening of the position of the Royal Greenwich Observatory. The providing of uniform time and its distribution by electrical means would support this cause. Airy had no interest to become involved in conflicts with stakeholders as this could only endanger his project. This is also reflected in his dealings with Alexander Bain. Bain objected to the electric clock system in Greenwich as it allegedly infringed his patents. After some correspondence with Bain’s solicitor, Airy gave the instruction to remove the words “Shepherd Patentee ...” on the dial of the Gate Clock. In his autobiography, Airy mentioned the dispute with Bain and stressed that there had been an extensive correspondence which, in hindsight, probably rather served as a justification for the removal of the lettering. Eventually Airy, to put it bluntly, dropped Charles Shepherd Jr. in this dispute. For him, the function of the clock system was more important than its builder. What impression might this have made on Shepherd? His electric clocks had powerful and influential enemies, and his “advocate” did not want to risk his own projects. Shepherd must have realised this after the patent dispute with Bain and the lack of support by Airy. A fresh start away from the petty squabbles in London must therefore have been very attractive for Shepherd. As we know, he seized his chance.

The sabotage of the slave clock, the attacks by Grimthorpe and the lack of backing by Airy seemed to have offended Shepherd despite the award by the Royal Society of Arts. This assumption is supported by the fact that nearly 25 years later, after Charles Shepherd Jr. had returned from India, he parried the attacks of his erstwhile opponents with new patents and proved with his new clock systems in Hornblotton and Oxford that his critics were wrong. They showed that with the help of electricity it was possible to move large tower clock hands, to strike bells, to secure a clock system against line breakage and to make even more precise master clocks. Besides, Charles Shepherd Jr. also greatly improved battery technology. In the person of the architect Sir Thomas Jackson he had found a supporter for his projects in Hornblotton and Oxford. Together they broke new ground: Shepherd in horology and Jackson in architecture, each a pioneer in his field. The fact that Airy's relationship with Shepherd had only been pure business was underlined by a reply to an inquiry by Shepherd: Shepherd wanted to introduce his new clock systems and asked for a short audience. Airy notified him in a note written by his assistant Criswick that he had no time.

Regarding Airy and his interests, one can only make assumption. His goal was probably primarily the strengthening of the position of the Royal Greenwich Observatory. The providing of uniform time and its distribution by electrical means would support this cause. Airy had no interest to become involved in conflicts with stakeholders as this could only endanger his project. This is also reflected in his dealings with Alexander Bain. Bain objected to the electric clock system in Greenwich as it allegedly infringed his patents. After some correspondence with Bain’s solicitor, Airy gave the instruction to remove the words “Shepherd Patentee ...” on the dial of the Gate Clock. In his autobiography, Airy mentioned the dispute with Bain and stressed that there had been an extensive correspondence which, in hindsight, probably rather served as a justification for the removal of the lettering. Eventually Airy, to put it bluntly, dropped Charles Shepherd Jr. in this dispute. For him, the function of the clock system was more important than its builder. What impression might this have made on Shepherd? His electric clocks had powerful and influential enemies, and his “advocate” did not want to risk his own projects. Shepherd must have realised this after the patent dispute with Bain and the lack of support by Airy. A fresh start away from the petty squabbles in London must therefore have been very attractive for Shepherd. As we know, he seized his chance.

The sabotage of the slave clock, the attacks by Grimthorpe and the lack of backing by Airy seemed to have offended Shepherd despite the award by the Royal Society of Arts. This assumption is supported by the fact that nearly 25 years later, after Charles Shepherd Jr. had returned from India, he parried the attacks of his erstwhile opponents with new patents and proved with his new clock systems in Hornblotton and Oxford that his critics were wrong. They showed that with the help of electricity it was possible to move large tower clock hands, to strike bells, to secure a clock system against line breakage and to make even more precise master clocks. Besides, Charles Shepherd Jr. also greatly improved battery technology. In the person of the architect Sir Thomas Jackson he had found a supporter for his projects in Hornblotton and Oxford. Together they broke new ground: Shepherd in horology and Jackson in architecture, each a pioneer in his field. The fact that Airy's relationship with Shepherd had only been pure business was underlined by a reply to an inquiry by Shepherd: Shepherd wanted to introduce his new clock systems and asked for a short audience. Airy notified him in a note written by his assistant Criswick that he had no time.

1853

In a dispatch dated 20 July, Charles Shepherd Jr. was appointed 1st Class Assistant to the Electric Telegraph (India).

1853

On 4 August, Charles Shepherd Jr. and his

wife Mary left

England from Southampton on board the Ripon destined for Alexandria.

(Fellow passenger were Harvey William Henry M.D. F.R.S., Irish

botanist, * 5 February 1811, Summerville/Ireland, † 15. Mai 1866,

Torquay, and Fürst Ernst zu Leiningen, nephew of Queen Victoria, * 9

November 1830, Amorbach/Germany; † 5 April 1904, Amorbach/Germany.)

1853

At the end of August, Charles Shepherd Jr. and his wife Mary embarked the Bentinck in Suez with the destination Kolkata/India. They arrived there at the end of September.

1854

On 15 August, Charles and Mary Shepherd's daughter Mary Louisa was born in Agra/India.

1855

On 8 January, Shepherd's wife Mary died in Agra at the age of only 29. This was a heavy blow of fate for him and could be the reason later for his professional difficulties in India.

The grave of Mary Shepherd in Agra

Photographer / Copyright: Gina Patczowsky

1855

In a dispatch from the Indian Telegraph Department dated 19 September, Charles Shepherd Jr.’s professional qualification was questioned.

1856

In a dispatch from the Indian Telegraph

Department dated 30 January,

further complaints about Charles Shepherd Jr. were uttered, leading to

his dismissal from service. The dispatches gave the impression that

Shepherd was the wrong person for the position he held and unable to

fulfil his tasks. However, this did not seem to be very convincing.

From 1849 to 1853, Shepherd had shown that he was able to successfully

implement many projects both theoretically and practically. The

building and installation of electric clock systems for Pawson in 1849

and the Great Exhibition in 1851, in Tunbridge Wells in 1852 and in

Greenwich in

1853 had proved his technical qualification as well as his ability as a manager. Furthermore, there were obviously no complaints for his first year (1854) in India. The telegraph line Kolkata–Agra (800 miles) had been completed within the year 1854; Shepherd had fulfilled his position. So what was the reason for his later failure? The death of his wife in January 1855 may have played a decisive role. This stroke of fate probably resulted in a nervous breakdown. He became unable to work. His superior O'Shaughnessy had had the same painful experience: On 30 August 1834 his first wife had died in Kolkata. Up to now, there have been no explanations forthcoming to either substantiate or contradict this criticism of Shepherd regarding his professional qualification.

1853 had proved his technical qualification as well as his ability as a manager. Furthermore, there were obviously no complaints for his first year (1854) in India. The telegraph line Kolkata–Agra (800 miles) had been completed within the year 1854; Shepherd had fulfilled his position. So what was the reason for his later failure? The death of his wife in January 1855 may have played a decisive role. This stroke of fate probably resulted in a nervous breakdown. He became unable to work. His superior O'Shaughnessy had had the same painful experience: On 30 August 1834 his first wife had died in Kolkata. Up to now, there have been no explanations forthcoming to either substantiate or contradict this criticism of Shepherd regarding his professional qualification.

1856? – 1861?

Mary Louisa Shepherd, Shepherd's daughter,

travelled from

India to England. In the 1861 census, she was recorded as having stayed

with her grandmother in London. Therefore she must have been brought to

England between 1856 and 1861. There are a number of possible reasons

as to why and when she was brought there. Possibly the daughter was

entrusted with friends returning to England in 1857. This would have

been a most practicable solution for Shepherd. He put his daughter in

the care of a foster mother and the costs would be more bearable.

Unfortunately the data for this period is very unsatisfactory.

Passenger lists from 1856 to 1857 are full of entries for women and

children returning from India to England. In many cases there are no

first names stated for the adults. For children no names were specified

at all, and very rarely is there any information as to kinship. The

climate in India was fatal for Europeans, especially during the monsoon

season. Indian colonial cemeteries bear witness to the early death of

many Europeans. Thus, it is not surprising that women and children

“fled” to England whenever possible. The Indian rebellion of 1857 to

1859 with its atrocities towards the European civilian population also

enforced this trend. There is an indication that Mary Louisa Shepherd

was brought to England by Mrs. O'Shaughnessy in April 1857. Mrs.

O'Shaughnessy was the wife of Richard O'Shaughnessy and a cousin of

William Brooke O'Shaughnessy.

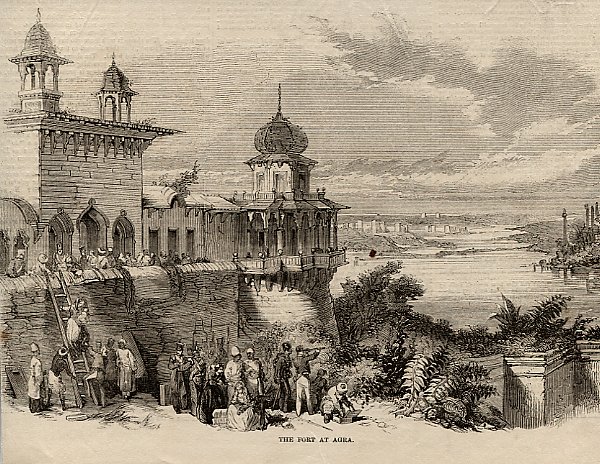

1857

The revolt in India against the British

colonial administration (Indian

Mutiny) began. If Shepherd had been residing in Agra at this time

(where his wife’s grave was), he would have been directly affected by

the events. We have evidence that a certain C. Shepherd, a

photographer, was member of the Agra Militia Infantry. The militia had

been established for the defence of the fort in Agra. At this time no

other person named Charles Shepherd was recorded residing in Agra.

The fort in Agra during siege by the mutineers.

Quelle: Archiv Denkel.

The fort in Agra during siege by the mutineers.

Quelle: Archiv Denkel.

1863

Charles Shepherd Jr. married Sophia Marshall

in Agra/India. It is

completely unclear as to when and why Sophia Marshall (his second wife)

had come to India. In the English census of 1851 (England) she is

listed as “assistant (dressmaker)”. In the 1861 census no further entry

concerning her person could be found. Had she already been in India at

this time? We also do not know how Sophia Marshall and Charles Shepherd

Jr. met.

What did Charles Shepherd Jr. do in India from 1856 until 1863 and later? What was his profession? What had he lived on? There was no question of him being re-employed by the telegraph administration nor by any other state institutions. His “failure” at the telegraph administration lead to this assumption.

For the time being let us put Charles. Shepherd Jr., the chronometer maker, aside and take a look at another Charles Shepherd likewise working in India. There was a well-known photographer by the name of Charles Shepherd working in Agra from 1857(?) until 1878. All sources refer to this period. There is no recorded data for the time before 1858 or after 1878. No date or place of birth and no date or place of death are given. There is also no mention of him having stayed outside India. It looks as though the photographer C. Shepherd did not exist before 1857 and after 1878. But a figure with such qualifications must have left his mark. He would not have appeared from nowhere and then disappeared again without a trace. However, if we superimpose the curricula vitae of the two persons, C. Shepherd, the chronometer maker, and C. Shepherd, the photographer, on top of each other, we end up with a consistent curriculum vitae for a single person. So are these two men one and the same person? Could it be that Charles Shepherd Jr. took up photography? How did he get in touch with this profession? It is known that his previous superior, O'Shaughnessy, was involved in photography at an early stage. Dr John Murray could also be the link to photography: Dr Murray initially worked as a doctor in Agra, at first for the East India Company and later in his own medical practice. From around 1849, he had been involved in photography and can be considered as one of the first photographers in India. During his time at the telegraph department in Agra, Shepherd might have met Murray and thus probably got in touch with photography. The fact that Charles Shepherd Jr., the chronometer maker, was open to new technology had been proved by his electric clock systems. At that time, photography was a new technology which offered enterprising possibilities for innovative individuals. Assuming these hypotheses are correct, Charles Shepherd Jr. had again shown how enterprising he was. His “failure” in the world of telegraphy had probably been a one-off most likely caused by the death of his first wife. In his article “Who was Charles Shepherd?”, Dr Alan Shenton explains that Charles Shepherd Jr.’s second wife Sophia was a photographer. Perhaps it was the other way around? Or were they both photographers? Unfortunately, Dr Shenton does not reveal his sources. In the 19th century, photographers’ wives often acted as assistants and published photographs under their own names. Dr Shenton also poses the question as to what happened to the photographs after they had died. If both Shepherds are one and the same person, this question can be answered partly. As far as India is concerned, there is a considerable amount of photographic material from this period available, but as far as private material is concerned, nothing is known of apart from a portrait of C. Shepherd, the photographer. The photographic studio Bourne & Shepherd in India owns photographs relating to India, whereas private photographs were probably taken to England. These photographs, assuming they existed, have been lost, just as there is nothing left from the other members of the Shepherd family. However, the search has just begun and one must not be daunted. There is hope that this article provides a new impulse for research into the history of the Shepherd family. Perhaps Shepherd’s photographic collection will turn up in a private collection.

What did Charles Shepherd Jr. do in India from 1856 until 1863 and later? What was his profession? What had he lived on? There was no question of him being re-employed by the telegraph administration nor by any other state institutions. His “failure” at the telegraph administration lead to this assumption.

For the time being let us put Charles. Shepherd Jr., the chronometer maker, aside and take a look at another Charles Shepherd likewise working in India. There was a well-known photographer by the name of Charles Shepherd working in Agra from 1857(?) until 1878. All sources refer to this period. There is no recorded data for the time before 1858 or after 1878. No date or place of birth and no date or place of death are given. There is also no mention of him having stayed outside India. It looks as though the photographer C. Shepherd did not exist before 1857 and after 1878. But a figure with such qualifications must have left his mark. He would not have appeared from nowhere and then disappeared again without a trace. However, if we superimpose the curricula vitae of the two persons, C. Shepherd, the chronometer maker, and C. Shepherd, the photographer, on top of each other, we end up with a consistent curriculum vitae for a single person. So are these two men one and the same person? Could it be that Charles Shepherd Jr. took up photography? How did he get in touch with this profession? It is known that his previous superior, O'Shaughnessy, was involved in photography at an early stage. Dr John Murray could also be the link to photography: Dr Murray initially worked as a doctor in Agra, at first for the East India Company and later in his own medical practice. From around 1849, he had been involved in photography and can be considered as one of the first photographers in India. During his time at the telegraph department in Agra, Shepherd might have met Murray and thus probably got in touch with photography. The fact that Charles Shepherd Jr., the chronometer maker, was open to new technology had been proved by his electric clock systems. At that time, photography was a new technology which offered enterprising possibilities for innovative individuals. Assuming these hypotheses are correct, Charles Shepherd Jr. had again shown how enterprising he was. His “failure” in the world of telegraphy had probably been a one-off most likely caused by the death of his first wife. In his article “Who was Charles Shepherd?”, Dr Alan Shenton explains that Charles Shepherd Jr.’s second wife Sophia was a photographer. Perhaps it was the other way around? Or were they both photographers? Unfortunately, Dr Shenton does not reveal his sources. In the 19th century, photographers’ wives often acted as assistants and published photographs under their own names. Dr Shenton also poses the question as to what happened to the photographs after they had died. If both Shepherds are one and the same person, this question can be answered partly. As far as India is concerned, there is a considerable amount of photographic material from this period available, but as far as private material is concerned, nothing is known of apart from a portrait of C. Shepherd, the photographer. The photographic studio Bourne & Shepherd in India owns photographs relating to India, whereas private photographs were probably taken to England. These photographs, assuming they existed, have been lost, just as there is nothing left from the other members of the Shepherd family. However, the search has just begun and one must not be daunted. There is hope that this article provides a new impulse for research into the history of the Shepherd family. Perhaps Shepherd’s photographic collection will turn up in a private collection.

1865

Charles Shepherd Sr., Charles Shepherd Jr.’s father, died at the age of 63 years in Rectory Cottage, Shacklewell, New Road. He is buried on Abney Park Cemetery, London. The widow of Charles Shepherd Sr., Mary Shepherd, became company owner and managed Shepherd & Son until her death in 1881.

1877/78

From 1878, data for Charles Shepherd

(chronometer maker) in

England/London is available. Charles Shepherd Jr.’s stay in India

probably ended in 1877/78. He returned to England together with his

wife Sophia.

1878

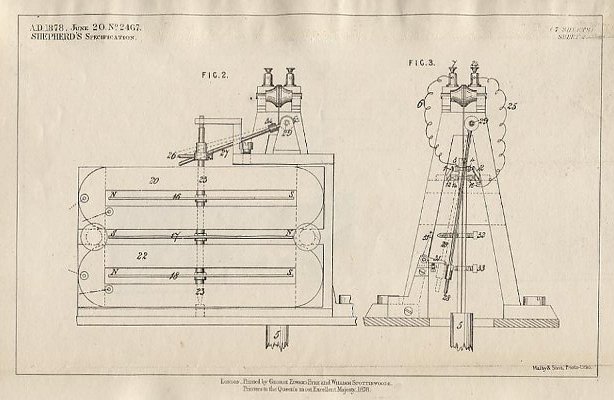

On 20 June, Charles Shepherd Jr. was granted

patent No. 2467

(“Improvements to Electro-Magnetic Clocks”). Address: 2 Alexandra Road,

South Hampstead. This was the first time that Charles Shepherd Jr. was

mentioned as living at this address.

Drawing / Patent No 2467

1882

Shepherd’s company was listed in the Post Office London Directory as “Shepherd Charles & Son, chronometer watch & clock manufacturers 53 Leadenhall street EC.” (source: Post Office London Directory,

1882. [Part 2: Commercial & Professional Directory], p. 1246).

1881

On 8 March, Charles Shepherd Jr.’s mother

Mary Shepherd died

in the Rectory Cottage. According to her will, assets of £1000 were

bequeathed to her eldest son Charles Shepherd Jr. She was buried on

Abney Park Cemetery, London.

1881

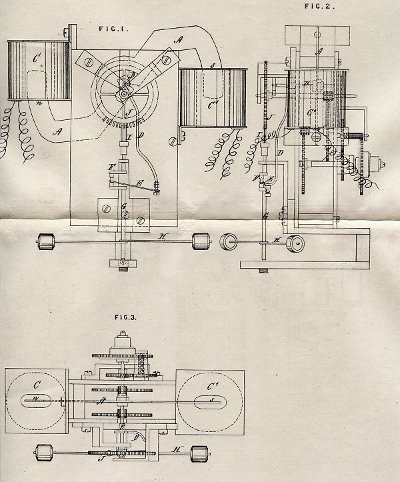

On 24 August, Charles Shepherd Jr. was granted patent No. 3696 (“Improvements to Electro-Magnetic Clocks and Batteries for same and other Porposes”).

Drawing / Patent No 3696

Charles Shepherd Jr. installed an electric tower clock system in the church of Hornblotton. Due to the lack of space in the tower, a traditional weight-driven tower clock could not be installed.

1883 / On 5 April, Charles Shepherd Jr. installed an electric master clock together with 19 slave clocks at the Examination Schools in Oxford. This installation was in operation until 1959.

1884 / The Shepherd company was listed in the Business Directory of London as “Shepherd & Son chronometer manufacturers 14 Talbot ct Gracechurch st EC.”.

1885

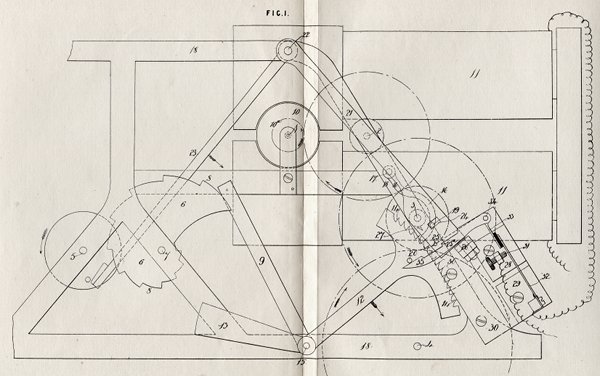

On 29. April, Charles Shepherd Jr. was granted patent No. 5308 (Improvements in Striking or Chiming Apparatus suitable for Time-keepers).

Drawing / Patent No 5308

1885

At the International Invention Exhibition, Charles Shepherd Jr. was endowed with a bronze medal for his electric tower clock.

1886 / On 20 December, Charles Shepherd’s brother, George Augustus, died at the age of 37 in London of tuberculosis. His last professional title was “Copyist in the Civil Service”.

1891

In the 1891 census (England), no entry could

be found for

Charles Shepherd Jr., his wife Sophia or the daughter from his first

marriage. Charles Shepherd Jr. and his wife may have travelled back to

India. For the years 1891 and 1892, we find entries in passenger lists

to India for Mr/Mrs and Miss Shepherd. Thus Charles Shepherd Jr. and

his wife Sophia (assuming that they are identical with the persons in

the list) were most probably no longer in England on 5 April (effective

date of the census). The long duration of the journey back to India

could be explained by stays in France or Egypt. On his first trips,

Charles Shepherd Jr. had probably been short of time, and he would not

have had the means for a stopover, for instance to do some sightseeing

tours in Egypt. But sightseeing trips like that were quite common among

wealthier people. Assuming Charles Shepherd Jr. and the photographer C.

Shepherd in Agra are the same person, the sale of his shares in the

Bourne & Shepherd studio would have given him the means to embark

on an extended trip. He had no business obligations in London any

longer. The company of Shepherd & Son had ceased to exist and two

brothers had died. So what would have kept him from going on an

extended educational trip to India via France, Malta and Egypt? He

could meet up with old friends and revisit at leisure all the places

where he had once stayed when he had been working in India. For his

wife Sophia, it was a chance to return to the places that had marked

important steps in her life. One of these places was Agra where she had

married Charles Shepherd Jr. in 1863. It is also conceivable that his

daughter by his first marriage, Mary Louisa, accompanied them, for

example to visit her mother’s grave in Agra. Charles Shepherd Jr. was

not recorded again in England until the census of 1901.

1894

On 15 February, there was an explosion

outside the Greenwich

Observatory. The reconstruction of the event showed that a bomb had

gone off in the hand of a male person. The injuries were so severe that

he died 30 minutes later without revealing his motives. Police

investigations concluded that it was Martial Bourdin, who had mixed

with anarchist groups in London. Further inquiries presented no other

findings for the general public, thus leading to all sorts of

speculation as to the motives for the crime. One such theory involved

the famous Gate Clock. Historically, public clocks were often regarded

as symbols of domination: “Wer die Zeit macht, hat die Macht” ( “He who

controls the time, controls the people”). A plot against the clock

could be interpreted symbolically as a plot against the power of the

state.

1905

On 1 July, Charles Shepherd Jr. died at the

age of 75 at 20

South Parade, Southsea, Hampshire. The cause of death given is dropsy

and exhaustion. He left his wife Sophia the sum of £402 19s. 5d.

Charles Shepherd Jr. was buried on Highland Road Cemetery in

Portsmouth. The grave still exist.

1909

On 4 June, Sophia Shepherd, Charles Shepherd

Jr.’s widow, died at 20

South Parade, Southsea, Hampshire. The cause of death given is apoplexy

and exhaustion. She left the sum of £617 13s. 5d. The beneficiary of

the will was her sister Caroline Marshall (*1832, †1913). Sophia

Shepherd was also buried on Highland Road Cemetery in Portsmouth. The

grave still exists.

Grave of Charles Shepherd and Sophia Shepherd.

© Hugh A. Rayner

|

In

Loving Memory of

CHARLES SHEPHERD.

THE BELOVED HUSBAND of

SOPHIA SHEPHERD.

BORN SEPTr 20TH 1829.

DIED JULY 1s 1905

ALSO OF THE ABOVE

SOPHIA SHEPHERD.

WHO DIED JUNE 4TH 1909

AGED 80 YEARS

|

Inscription on the grave stone of the grave

of Charles and Sophia Shepherd.

of Charles and Sophia Shepherd.

The author would be very interested in finding relatives of the family Shepherd / Osmond / Marshall / Hulse to complete the family history. If you have information relating to the listed persons below / families or know of any relatives please contact the author by e-mail.

info@alte-zeitmesstechnik.de

Full discretion is guaranteed ! Please help in preserving the Shepherd family history for the future.

- Charles Shepherd

- (known addresses: 53 Leadenhall St. / London, Alexandra Road / London, South Parade / Southsea)

- Mary Louisa Shepherd (daughter of Charles Shepherd)

- lived in Kent (1911 / Whitstable Tankerton).

- William Henry Shepherd

- (known addresses: 53 Leadenhall St. / London, 115 Albion road Stoke Newington, 11

- Railway place / London)

- Osmond

- (known adresses: 99 Leadenhall St. / London)

- Marshall

- (Easenhall / Monks Kirby)

- Hulse (Richard Hulse, Hulse and Nephew)

- Hinckley / London Leadenhall st. / Agra / Ajmere / India

Appendix

Shepherd (chronometer-maker) Shepherd (photographer)

Meanwhile a document has been found which proves (together with other information), that the both Shepherds are identical persons.

Register of death, Sophia Shepherd, 14. June 1909: "Widow of Charles Shepherd formerly a Photographer"

Master clocks made by Shepherd

1849 Pawson's Warehouse, London.

1851 Crystal Palace / Great Exhibition, London.

1852 Royal Greenwich Observatory, London.

1852 Tunbridge Wells.

1854 Coastal Tower Deal.

1854 Ellis Observatory Ellis / Guildhall, Exeter.

1858 Williamstown Observatory, Melbourne (Australia).

1859 Observatoire Cantonal de Neuchatel (Switzerland).

1869 Coloba Observatory, India.

1872 Madras Observatory, India.

1883 Rectory/ Church, Hornblotton.

1883 Examination Schools, Oxford.

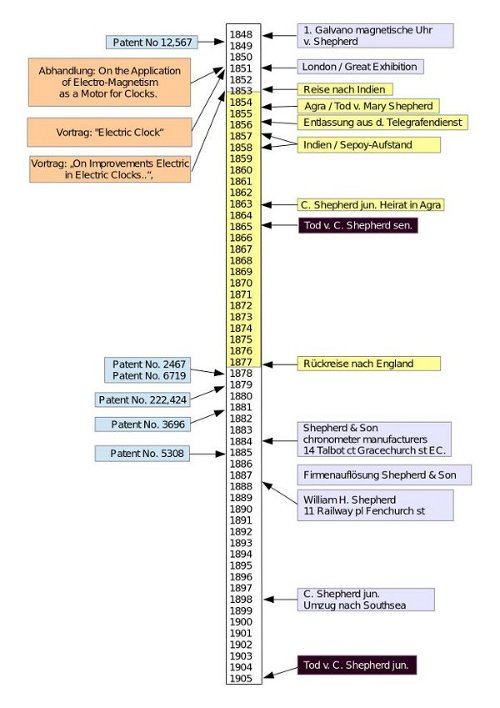

Chronology patents

The graph clearly shows the large gap in time where no patent activities or events by C. Shepherd Jr.. can be found. This is another indication of a continuous stay of Shepherd in India. After his return in 1877 he began to be active in the field of electric clocks.

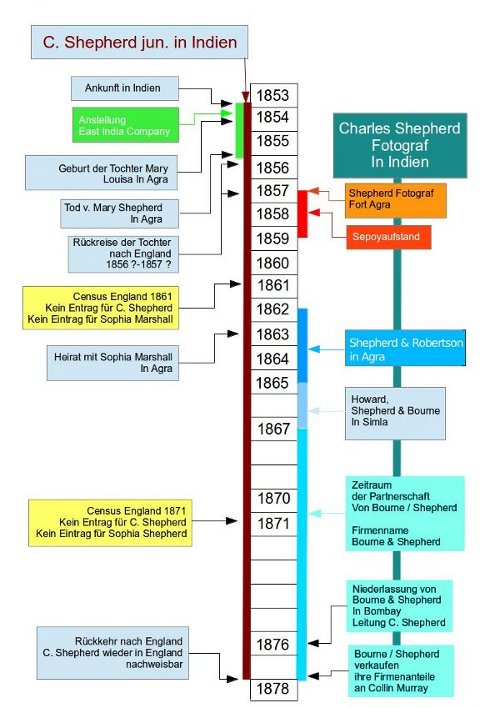

Shepherd in India

the arrows indicate the times Charles Shepherd jun. stayed in India from 1853 to 1878 (left column)

Charles Shepherd Photographer (right column)

Bibliography

C. Shepherd

- Charles Shepherd: On the Application of Electro-Magnetism as a Motor for Clocks, London 1851.

- F. G. Alan Shenton: Who Was Charles Shepherd?, in: AHS. Nr. 5, Vol. 21, Autum1994, S. 438–445.

- Denys Vaughan: Charles Shepherd's Electric Clocks, in: AHS. Nr. 6, Vol. 21,Winter 1994, S. 519–530.

- Robert Miles: The Early Clocks of Charles Shepherd, Lecture for the AHS Group, 18th Sep. 1999.

- A. Mitchell and D. F. Nettell: AN ELECTRIC TURRET CLOCK BYSHEPHERD, in AHS, Vol. Autum 1977 S.463.

- Eugen Denkel: Charles Shepherd jun., Chronometermacher, Ingenieur, Erfinder, Fotograf. Zum 110 Todesjahr, Anmerkungen zu Leben und Werk. In: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Chronometrie, Jahresschrift 2015, Band 54, S. 181-194.

Clocks

- Tony Mercer: Chronometer Makers of the World. N.A.G. Press, London 2004.

- Roberts Derek: Precision pendulum clocks: the quest for accurate timekeeping, Atglen PA 19310, 2003.

Electrical clocks

- Charles K. Aked: Electric clock patents from the 19th century Clocks August 1986.

- Charles K. Aked: Electricity, Magnetism and Clocks; in: Journal of the RoyalNaval Sientific Service, Vol. 26, 1971.

- Alexander Bain's Short History of the Electric Clock (1852), edited by W. D.Hackman, London, 1973.

- The Examination Schools Conservation Plan, April 2012, Building No. 155, Oxford University Estates Services, First draft February 2011, This draft April 2012 .

- Charles Vincent Walker: On Controlling Clocks by Electricity; in: Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Vol. 21, p.72, 1861.

- Langmann H.R., Ball A.: Electric Horology, London 1927, S. 148-150.

- Frank Hope-Jones: Electrical Timekeeping, London, 1976, ISBN 7198 0070.

Astronomy

- Ichsanova Vera: Pulkovo / St. Petersburg, Spuren der Sterne und der Zeit, Geschichte der russischen Hauptsternwarte, Frankfurt/M 1995, ISBN 3-631-49253-7.

- Repsold Joh. A.: Zur Geschichte der Astronomischen Messwerkzeuge, 2 Bände, Leipzig 1908 / 1914.

- Herbst Klaus D.: Die Entwicklung des Meridiankreises 1799-1850, 1996.

- Howse, Derek. (compiled by): The Greenwich list of observatories: A world list of astronomical observatories, instruments and clocks, 1670–1850, 1986.

- Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy. Edited by Wilfrid Airy. , Cambridge, University Press, 1896.

Greenwich Observatory

- Douglas Bateman: The time ball at Greenwich and the evolving methods of control, Part 1-3, AHS Vol. 34, June 2013, September 2013, December 2013.

- Douglas Bateman: The replacement of the war-damaged Shepherd dial at Greenwich by James Cooke & Son of Birmingham, in AHS No. 1, Vol. 36, S. 84- 90.

- T. Lewis: The Greenwich system of sympathetic clocks and the distribution of time-signals, in: The Observatory, Vol. 8, (1885).

- Gilbert E. Satterthaite: Airy's zenith telescopes and "the birth-star of modern astronomy", in: Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage 6 (1) 13-26, 2003.

- P.S. Laurie: The buildings and old instruments of the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, The Observatory, Vol. 80, p. 13-22 (1960).

- Airy, G. B.: Plan of the Buildings and Grounds of the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, 1863, August; with Explanation and History, in: Greenwich Observations in Astronomy, Magnetism and Meteorology made at the Royal Observatory, Series 2, vol. 24, pp.F1-FPIV.

- Howse, Derek: (1997) Greenwich Time and the Longitude, Official Millennium ed., London : Philip Wilson, National Maritime Museum, ISBN 0-85667-468-0.

- E. Walter Maunder FRAS: The Royal Observatory, Greenwich: A Glance at its History and Work, The Religious Tract Society, London, 1900.

- Meibauer R. O. Dr.: Die Sternwarte zu Greenwich, Berlin, 1868.

- Smith, R. W.: A National Observatory Transformed - Greenwich in the Nineteenth Century, in: Journal: Journal for the History of Astronomy, Vol.22, NO. 1/FEB, P. 5, 1991.

- Wilkins George A.: A Personal History of the Royal Greenwich Observatory at Herstmonceux Castle, 1948 – 1990, Volume 1 – Narrative / Volume 2 – Appendices.

- Marshal Tyler: Clocks at Greenwich Running Down: It's Later Than You Think for World's Timekeeper, In Los Angeles Times, August 10, 1987.

- Howse D.: Greenwich Observatory: Buildings and Instruments, London, 1975.

- Site of the Royal Observatory, in: THE RAILWAY MAGAZINE; and Annals of Science. No. II. APRIL. 1836.

- LONDON LETTER, S. 48, in: STREET RAILWAY JOURNAL. Vol. XXVIIL No. I. 1906.

- William Sheehan, Nicholas Kollerstrom, Craig B. Waff: Die Neptune-Affaire, in: Spektrum der Wissenschaft, April 2005, S. 82-88.

- Barry A. J. Clark, PhD, Early Colonial Electris: Clocks, Chronograph, Relay, Bell and Telescope jn the South Equatorial House at Melbourne Observatory 2011.

- Lucien F. Trueb / Pierre Favre: L'Observatoire de Neuchatel, Son Histoire de 1858 a 2007, Neuchatel 2000, ISBN 978-2-9700775.2.7.

- L'Observatoire cantonal neuchâtelois 1858-1912.

- Babey, Virginie: L'Observatoire chronométrique de Neuchâtel: evaluation et évolution dûne société de services à travers ses instruments scientifiques, de la deuxième moitié du 19e à la première moitié du 20e siècle , in: Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Wirtschafts- und Sozialgeschichte , Band (Jahr): 22 (2007).

Time Distribution

- David Rooney and James Nye: Greenwich Observatory Time for the public benefit, in: The Journal for the History of Science, Vol. 42, Issue 01, March 2009, S. 5-30.

- Hannah Gray: Clock Synchrony, Time Distribution and Electrical Timekeeping in Britain 1880-1926, in: Past & Present, No. 181, November 2003.

- John A. Chaldecott: Platinum and the Greenwich System of Time Signals in Britain, in: Platinum Metal Rev., 1986, 30, (1).

- Waldon Fawcett: Distribution of Time Signals, in: The Technical World, March, 1905.

- Leland Hite: How Time Balls Worked. 2014. Deal Time Ball.

- Charles F. C. Beresford and John H. Combridge: THE DEAL TIME BALL, AHS, Vol. 19, Autum 1990. S. 33-43.

- Ponsford, Clive N.: Devon clocks and clockmakers, Vermont 1985, ISBN 0-7153-8332-9.

- Ponsford, Clive N.: Time in Exeter, Exeter 1978, ISBN 0 9506361 0 X.

- Saroj Ghose: William O'Shaughnessy - an Innovator Intrepreneur, in: Indian Journal of History of Science 29 (1) 1994.

London

- Metropole London, Ausstellungskatalog, Hrsg: Kulturstiftung Ruhr Essen, Recklinghausen, 1992, ISBN 3-7647-0427-6.

- Loftie W. J.: London City, Its History-Streets-Traffic-Buildings-People, London, 1891.

- John Tallis's, London Street Views, 1838-1840, London Topographical Society, Bury St. Edmunds, 2002, ISBN 0902087479.

- Peter Brimblecombe: The Big Smoke, History of Air Pollution in London Since Mediaeval Times. Cambridge 1987, ISBN 0-416900801.

- Lee Jackson: Dirty Old London, The Victorian Fight Against Filth, Padstow 2014, ISBN 978-0-300-1920-6.

India

- Overland Route to India and China, London 1859.

- John Brinton: Mr. Waghorn's Route to India, in: Saudi Aramco World, November / December 1968, Vol. 19, No. 6.

- C. W. Brebner: New Handbook for the Indian Ocean, Arabian Sea and Bay of Bengal..,Printed at the Times of India Press, 1898.

- R. M. Coopland: A lady's escape from Gavalior and life in

the Fort of Agra during the mutinies of 1857, Elder and Co., 1859.

- Christopher Hibbert: The Great Mutiny India 1857, London

1978, ISBN 0 7139 1054 2

- Stephen Rayner: Set in stone, The hero who took a shortcut, in: Medway News, Memories page, 7 February 2004.

- Robin Volkers: Agra Cantonment Cemetery, BACSA Putney, London, 2001, ISBN: 0907799760.

- Shekhar Krishnan: Empire's Metropolis Money Time & Space in Colonial Bombay, 1870-1930, MIT 2013.

- Harvey William H.: Memoir of W. H. Harvey, M.D., F.R.S., etc., etc., late professor of botany, Trinity College, Dublin. With selections from his journal and correspondence, London 1869.

- Sophie C. Ducker: The Contented Botanist, Letters of W. H. Harvey about Australia and the Pacific, Brunswick 1988, ISBN 0522843417.

- David Waldie: Journal of a Voyage from England to Calcutta by the Overland Route, 2013.

- Grindlays & Co., Hints for Travellers to India, London 1847.

This Internet article is a short summary of the main points from the German book series (private edition / non-commercial) “Charles Shepherd junior, 1829–1905, Chronometermacher Ingenieur Erfinder Fotograf”, Volume 1–2, by Eugen Denkel.

- Eugen Denkel: Charles Shepherd jun. London .... / Band I / Datensammlung zu Leben, Werk, Personen und Wirkungsstätten, Privatdruck 2015, 334 S.

- Eugen Denkel: Charles Shepherd jun. London .... / Band II / Patente, Historische Texte, Nachträge zu Band I, Privatdruck 2017, 394 S.

About the Author

Professional career in the field of

research and development of aids

for shipping navigation (radio navigation, precision timekeeping, radio

beacons). Worked furthermore in the field of public relations and

historical research for a German administrative body. After retirement

research on Charles Shepherd Jr. In 2015

publication of a book series in German on

Shepherd (“Charles Shepherd

junior, 1829–1905, Chronometermacher, Ingenieur Erfinder Fotograf”,

Vol. I). In 2015 publication of an

article on Shepherd in “Jahresschrift der

Deutschen Gesellschaft für Chronometrie”. Further publications about

Franklin clocks and clock-making in Germany. In 1992, contributor and

author to an exhibition in Koblenz, Germany:

“Meisterwerke – 2000 Jahre Handwerk am Mittelrhein” (Masterpieces of

2000 years of artisanship in the Middle Rhine region). In 2003

contributor and co-author of the catalogue “Kinzing & Co,

innovative Uhren aus der Provinz” (Innovative clocks from the province)

for the Roentgen Museum in Neuwied, Germany. Patentee of an electric

rolling ball clock. Operates a private

astronomical observatory.

v-3-2017-01-01 / v-3-2018-01-03zurück zur Artikelübersicht...

top

Ian D. Fowler

Am Krängel 21, 51598 Friesenhagen

Germany

Tel. +49 (0) 2734 7559

Mobil 0171 9577910

e-mail Ian.Fowler@Historische-Zeitmesser.de

Am Krängel 21, 51598 Friesenhagen

Germany

Tel. +49 (0) 2734 7559

Mobil 0171 9577910

e-mail Ian.Fowler@Historische-Zeitmesser.de

Letzte Aktualisierung 01.03.2018