Ian D. Fowler FBHI

Uhrenrestaurator u. Uhrenhistoriker

Uhrmacher Biographien

Shepherd / London

New Data to Family- and Company History

Part 1

Eugen Denkel

Translation from German by Svenja Viola Bungarten

New Data to Family- and Company History

Part 1

Eugen Denkel

Translation from German by Svenja Viola Bungarten

In 2015 an article about the

London based Shepherd family of watch makers / chronometer makers was

published in DGC annual magazine to mark the 110th anniversary

of the death of

Charles Shepherd Jr. The article dealt with the main points concerning

the history of Shepherd

with special reference to Charles Shepherd Jr and reported based on the

level of knowledge in

2014. In the past four years, additional sources have been evaluated

that complete the previous

picture, but also reveal new facets. They apply to the number of

electrical clock systems, their

scope, and thus also the importance of the Shepherd company. The most

important new data are

presented below as a supplement and update of the previously mentioned

article from 2015.

Let us begin with Charles Shepherd Sr, who was first mentioned as a

watchmaker in connection

with the 1841 census and several fire policies. The policies

(1830-1836) do reflect a steadily

growing economic success of Shepherd. The sum insured increased from £

200 in 1830 to £ 400

in 1834 and £ 900 in 1836. Glass and porcelain, which were still a

luxury item at the time, are

also listed in the policies - as well as a work shop and materials

behind the house (Chadwell St)

for the year 1836. It seems noteworthy that books are listed in the

policies as well.

Fig. 1

Chadwell Street / No. 7 (yellow brick wall) residence and workshop of Charles Shepherd Sr. before moving to Leadenhall St. © Denkel 2017

Chadwell Street / No. 7 (yellow brick wall) residence and workshop of Charles Shepherd Sr. before moving to Leadenhall St. © Denkel 2017

The move from Sydner St to

Chadwell St (around 1830) was most probably due to the economic

success of Shepherd, as Chadwell St was a much better address than the

somewhat narrow Sydner St. We have reason to believe that the earliest

known Shepherd

chronometer with serial no. 126 originates from this time. Two other

chronometers, with the

numbers 132 and 134, are documented for the year 1835. (Chronometer

trial 1835). The number with

which Shepherd began numbering his chronometers is unknown. Presumably,

according to

general practice, this was probably not the number 1, but rather the

100 or 101.

Thus the above chronometer would be the 26th chronometer made by

Shepherd. Furthermore, it seems relevant that London is the only given

location on the dial,

without the indication of a street. There is no engraving to be found

on the backplate. The early

serial number and the lack of a street name suggest that the

chronometer dates back to when

Shepherd lived and worked on Sydney St or Chadwell St. We know of

Chadwell St that Shepherd had a

workshop there. Both addresses were outside of the city, both

residencies had no business

premises with shop windows, as they were primarily residential

buildings. Due to the

location outside the business center of London and considering a later

settlement in the City of

London, it makes no sense to give a street specification at this time.

The lack of a street name also supports another assumption. We know that Shepherd's predecessor at 53 Leadenhall St, Christopher Rowlands, was a watchmaker as well. Rowlands is not known to have built chronometers. However, he may have collaborated with Shepherd and sold his chronometers, presumably a win-win situation for both parties. The fact that Shepherd took over the premises at 53 Leadenhall is another strong indication of contact and possibly an earlier collaboration between the two. An advertisement in the Shipping and Mercantile Gazette from October 19, 1847, regarding the auction (... at Lloyd's Captains' Room, Royal Exchange) of two ship chronometers (Poole, Thornby) gives us first indications of direct business activity from the address 53 Leadenhall St. The auction objects could be sighted in advance at this very same location. For 1849 we find a similar advertisement regarding the auction of a Poole chronometer, also previewed at Shepherd. He might have moved to 53 Leadenhall St, next to the Cock Inn, around 1844/45.

The lack of a street name also supports another assumption. We know that Shepherd's predecessor at 53 Leadenhall St, Christopher Rowlands, was a watchmaker as well. Rowlands is not known to have built chronometers. However, he may have collaborated with Shepherd and sold his chronometers, presumably a win-win situation for both parties. The fact that Shepherd took over the premises at 53 Leadenhall is another strong indication of contact and possibly an earlier collaboration between the two. An advertisement in the Shipping and Mercantile Gazette from October 19, 1847, regarding the auction (... at Lloyd's Captains' Room, Royal Exchange) of two ship chronometers (Poole, Thornby) gives us first indications of direct business activity from the address 53 Leadenhall St. The auction objects could be sighted in advance at this very same location. For 1849 we find a similar advertisement regarding the auction of a Poole chronometer, also previewed at Shepherd. He might have moved to 53 Leadenhall St, next to the Cock Inn, around 1844/45.

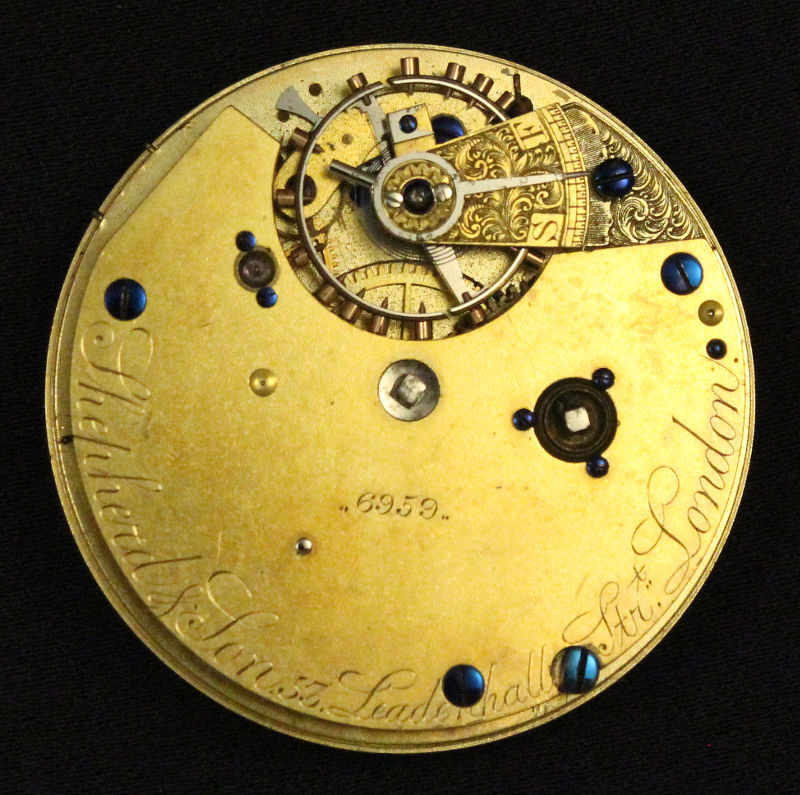

Fig. 2

Fragment of a pocket watch movement by Christopher Rowlands

53 Leadenhall St / London.

© 2019 Denkel

Fragment of a pocket watch movement by Christopher Rowlands

53 Leadenhall St / London.

© 2019 Denkel

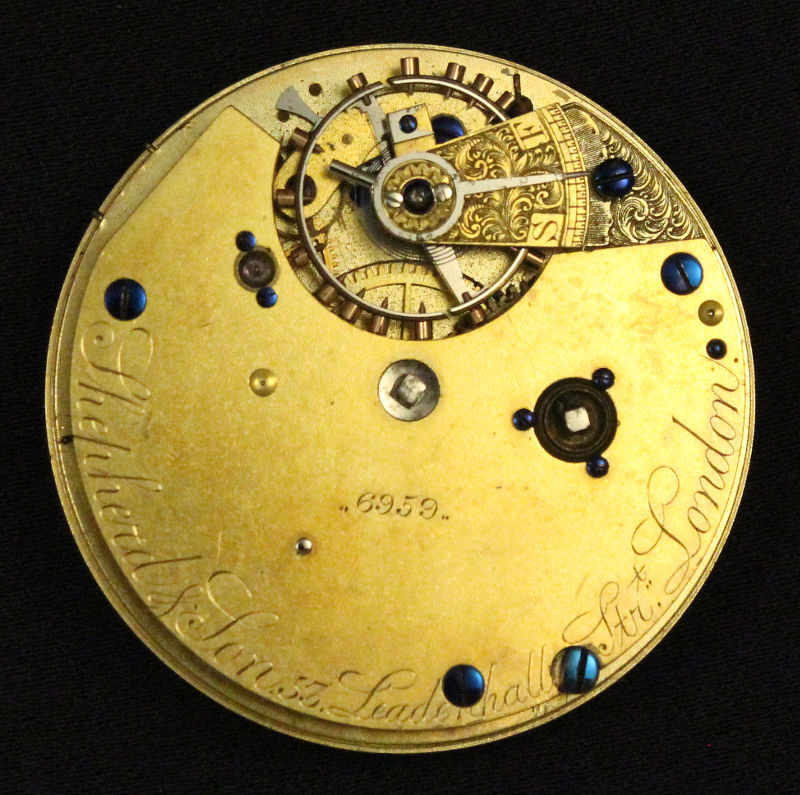

Fig. 3

Fragment of a pocket watch movement by Shepherd & Son

53 Leadenhall St / London.

© 2019 Denkel

Fragment of a pocket watch movement by Shepherd & Son

53 Leadenhall St / London.

© 2019 Denkel

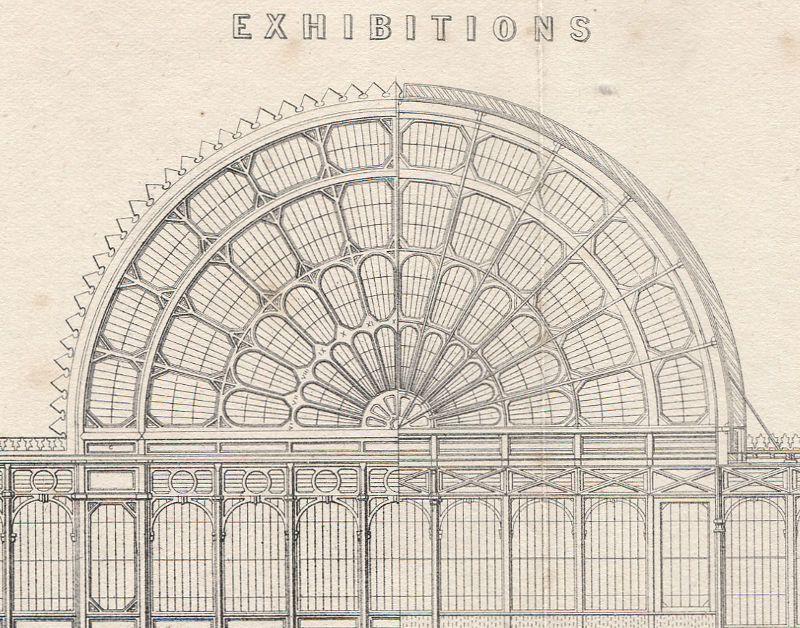

The story of the "failure" of

the Shepherd electric clock system in the Crystal

Palace (Great Exhibition 1851), appears quite frequently in given

horological literature.

Grimthorpe is often given as the source. But Grimthorpe is not an

impartial reporter on the matter, as

he competed with Shepherd’s tower clock designs. Two contemporary

newspaper articles are

likely to contradict his statements regarding Shepherd's electric

clocks, which he published

several times in his books. The reason for his portrayal was probably

an act of sabotage

against Shepherd's electrical clock system during the exhibition. The

Illustrated London News of

August 23, 1851 reports on this event:

|

"The great clock, notwithstanding the

large surface,

exposed to the wind, and the recent high gales, has continued to mark

the time satisfactorily. We

regret, however, to record that some mischievous or malicious person

has cut the wires, on one or

two occasions, which communicated the power to the dial in the Western

Nave, and the same

clock, having received some injury, has not performed as well as its

more noble companion."

|

Furthermore, the Northern Whig (October 16, 1851) reports from the closing ceremony:

|

"The civil and military bodies continued

to close upon the rear, and the passive

resistance became weaker and weaker. The electric clock was half-past

six as the last invader was driven from Paxtonia."

|

According to this,

the large external clock on the transept was in function and with it

the rest of the Shepherd clock

system. This also contradicts the impression that Shepherd's electrical

clock system was a

"failure" which Grimthorpe tried to convey in his book: A Rudimentary

Treatise on Clocks, Watches and Bells.

Fig. 4

Crystal Palace / South Transept / London 1851

Architectural drawing (detail) with the large Shepherd clock.

Archiv Denkel

Crystal Palace / South Transept / London 1851

Architectural drawing (detail) with the large Shepherd clock.

Archiv Denkel

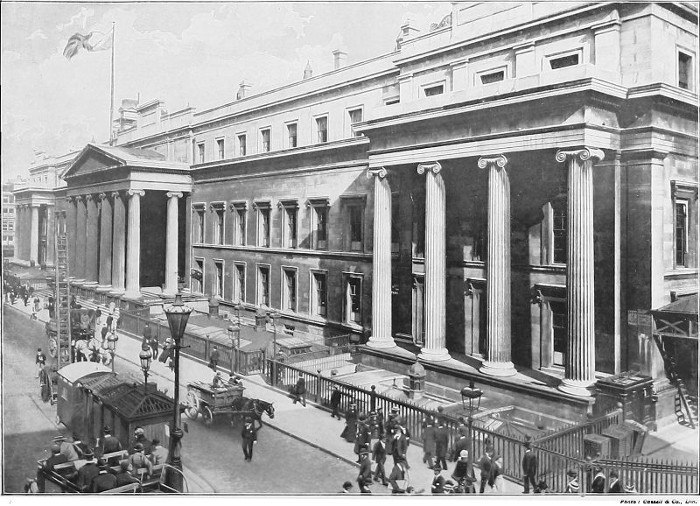

Detailed information on

Shepherd's work in connection with the tower

clock (built by Vulliamy)

in the General Post Office in St. Martin’s-le-Grand can be found in an

article in the Morning

Advertiser of January 2nd, 1857, entitled:

| “THE EXTENSION OF

THE ELECTRO- MAGNETIC SYSTEM TO THE GOVERNMENT OFFICES”. To bring in a

short section of the much more extensive article, concerning the tower

clock: "...The reason it has not been "going“ lately is, as we have

before observed, not owing to any mere cleaning. It has been taken down

and cleaned by Mr. Charles Shepherd, of Leadenhall-street; but it could

not put again into operation in consequence of arrangements which were

in progress for connecting the whole of the clocks in the General

Postoffice—which are nearly 100 in number, including those in the

money-order chief office, on the other side of the way into

electro-magnetic correspondence with the Royal Observatory at

Greenwich, in order that they may not only invariably agree amongst

themselves, but also, the same time, invariably indicate Greenwich mean

time. The advantages of this arrangement are so multitudinous and so

obvious that we need not enter into any detailed indication of them.

The system, once in operation at the Post-office, will be subsequently

extended, by Mr. Shepherd, under the direction of the Astronomer Royal,

to Somerset House, where there are about 150 clocks, and finally to

every Government office throughout the metropolis. In fact, the

ultimate object of the Government is, as far as possible, to extend

this system to every Government office throughout the kingdom, so that

the opponents of “centralisation” will actually have to appeal to the

Government authorities to determine "the time of day !" |

| The article adds: |

| “Mr.

Charles Shepherd,

chronometer maker to the Royal navy, to whom, under the Astronomer

Royal, is entrusted the execution of this project,

is the patentee of the Electro-Magnetic Striking Clock, specimens of

which may seen in Lombard-street, at the South-Eastern Railway, and the

Royal Observatory, Greenwich.“ |

The

newspaper article contains

some

information about the Shepherd company, the most important statements

below in keywords: Charles Shepherd Sr was commissioned with the

cleaning of the tower clock. The clocks (approx. 100 pieces) inside the

building, as well as the clocks in the building on the other side

of the street, should be electrically connected in such a way that all

clocks show exactly Greenwich mean time."

Fig. 5

THE GENERAL POST OFFICE, LONDON.

Quelle:The Queen's Empire. Volume 3. Cassell & Co. London (1887-99) / by Wikimedia commons. Licence: Public Domain

THE GENERAL POST OFFICE, LONDON.

Quelle:The Queen's Empire. Volume 3. Cassell & Co. London (1887-99) / by Wikimedia commons. Licence: Public Domain

Shepherd's clock system was

also to be

installed in Somerset House (150 clocks). The astronomer Royal George

B. Airy is named as a

project manager. The clock system in the General Post Office was

divided into four clock

groups. Each group consisted of a master clock (here called father

clock) with associated

slave clocks. These master clocks were each monitored and regulated by

Greenwich. The electrical

clock system in Lombard St was working, a clock system was to be

installed in the House

of Parliament (note: was not implemented). It is pointed out in detail

that Shepherd has

been entrusted with the execution of the project. The astronomer Royal

Airy also indirectly

mentions this project in his autobiography by writing in the year 1855:

| "I have arranged constructions which possess these characters, and the artist (Mr. C. Shepherd) is now engaged in preparing estimates of the expense. I think it likely that this may prove to be the beginning of a very extensive system of clock regulation ”. |

| For 1856, he records: |

|

”With respect to the regulation of the

Post

Office clocks, 'One of the galvanic clocks in the Post Office

Department, Lombard Street, is

already placed in connection with the Royal Observatory and is

regulated at noon every day ...other

clocks at the General Post Office are nearly prepared for the same

regulation, and I expect

that the complete system will soon be in action.”-

|

Shepherd's work for various

London authorities is also reflected in a

form / invoice sheet from Shepherd, originating in the time when

William Henry Shepherd took

on the company after the death (1881) of his mother Mary Shepherd. As

noted in the

letterhead Shepherd & Son were Clock Makers to the General Post

Office & Custom House

and Indian Government as well as Electric Clock Makers to the Royal

Observatory. The Custom

House building on the banks of the Thames still stands today, with a

dial showing in the gable.

Fig. 6

Custom House / London seen from the River Thames.

Shepherd was "Clockmaker to the General Post Office & Custom House."

© 2019 Denkel

Custom House / London seen from the River Thames.

Shepherd was "Clockmaker to the General Post Office & Custom House."

© 2019 Denkel

Shepherd had also installed an

electrical clock system in the post

office in Lombard St for test purposes. The Morning Advertiser of March

26, 1856 reports about it:

"On Saturday a new striking clock, constructed on a novel principle,

called the galvanomagnetic clock, was erected

at the Post-office, Lombard-street." It is remarkable to note that it

was a "striking clock", i.e. a

clock with an electric striking mechanism. Absurd, had Grimthorpe not

written that electricity

was incapable of lifting anything of weight? Grimthorpe's arguments

against Shepherd can be

seen as an indication of how seriously he viewed Shepherd as an

economic competitor.

Shepherd's clock systems and their scope also show the importance of the Shepherd family and their company in the mid-19th century. Shepherd was the industry leader. Additionally, Charles Shepherd Sr’s role in the field of electrical clocks needs a positive reassessment, as he continued to be successful in the field of electrical clock systems during the absence of his son Charles (who was in India). The convocation (1851) of Charles Shepherd Sr into the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures, and Commerce supports the assumption that he played an important role in the field of electrical clocks (alongside his son Charles Jr).

Shepherd's clock systems and their scope also show the importance of the Shepherd family and their company in the mid-19th century. Shepherd was the industry leader. Additionally, Charles Shepherd Sr’s role in the field of electrical clocks needs a positive reassessment, as he continued to be successful in the field of electrical clock systems during the absence of his son Charles (who was in India). The convocation (1851) of Charles Shepherd Sr into the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures, and Commerce supports the assumption that he played an important role in the field of electrical clocks (alongside his son Charles Jr).

In

1860 a litigation between Charles Shepherd Sr and his foreman Daniel

Mapples unfolded.

This process received a lot of coverage in the London press, which

probably would not have been the case if Shepherd had been an

insignificant personality.

Shepherd thereafter dismissed Daniel Mapples with immediate effect for

violating the statutes of his employment contract.

Mapples sued the Mayor of London for the circumstances of his dismissal

and demanded that his wages be paid for 14 days. His lawsuit was

dismissed.

One

other source that mentions Shepherd’s foreman in connection with the

procurement of a new clock

for St John's in Exeter should furthermore be consulted. Shepherd had

sent his foreman to Exeter to answer questions from the Improvement

Commission there. The Trewman's Exeter Flying

Post, dated April 6, 1854 reports:

| “The St. John's Clock.- A meeting of the St. John's Clock Committee was held last evening, when it was stated that the foreman of the patentee of the electric clock, (Mr. Sheppard) had visited the city, and reported favourably on the establishment of an electric clock at the Guildhall which might be placed in connection with that at the Cathedral and other public clocks...“. |

The

St. John's Church in Exeter belonged to the smaller churches in Exeter.

In

1844/45 the dial was added a second minute hand. This enabled the clock

to display both Exeter local time and Railway Time (Greenwich mean

time).

In 1853 a request for the purchase of an electric clock was made to the

Improvement Commission by the parish of St John's. The old clock often

showed the

wrong time or stood still. A debate began that extended over a long

period of time as to which type of clock should be purchased. A

conventional, purely mechanical tower clock or an

electrical clock, which should then also be controlled by the existing

Shepherd clock in the Guildhall was up for discussion.

The proponents of the new technology, an electric clock, could not

prevail. All arguments, including a letter from Airy, did not help;

Dent received the order.

Regrettably, no electrical clock was procured, but the correspondence

nevertheless is of great value, as various information about Shepherd

and his clocks were given

there. It is mentioned that Shepherd supplied a 6-foot high external

dial for the city of Chester and that it was to be installed. "Who is

now erecting a 6 feet dial for the city of Chester ..".

We

also find an exact indication of the number of

Galvano-Magnetic-Regulators delivered to India for the local telegraph

administration: “has by this mail

forwarded 4 electric normal

regulators to India“ (December 15,

1853, Exeter Flying Post). It was also previously unknown that the

Western Railway Company in

Paddington was planning to purchase an electrical clock system from

Shepherd.“and that the

Great Western Railway Company are about to adopt the like system for

their extensive premises at Paddington.“ We can only speculate

about the premises (train station? Or administration

building?).

Thanks

to the initiative of Henry Samuel Ellis (watchmaker in Exeter), besides

Greenwich / London, Exeter was one

of the pioneers in the field of electrical clock systems. In 1854,

Shepherd

supplied a Galvano-Magnetic-Regulator for the Guildhall in Exeter. It

was converted in 1891 by F. T. Reid, a watchmaker from Exeter, to

weight drive and graham escapement, all electrical components were

removed. The original dial

bears the number 48. Accordingly, by the time this clock was finished,

another 47 electro-magnetic regulators should have been made by

Shepherd. An illustration, in connection with an article by Ellis from

1854,

shows the regulator in an architecturally designed wall niche, which

remains undiscovered until today. The question of the exact location of

the Shepherd clock within the Guildhall was answered by an

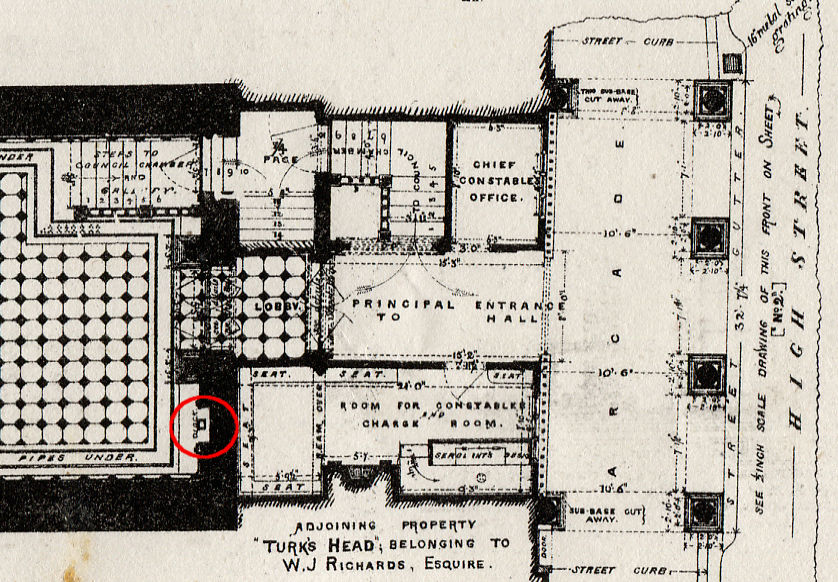

architectural drawing/floor plan from 1875. The clock is

marked on this floor plan, in a prominent place, which should underline

its importance. The red circle shows the niche in the wall with the

small rectangle that the Shepherd clock indicates. Heading that, barely

decipherable, the written entry Clock. This niche can no longer be

found on later interior shots of the Guildhall, as it is covered by

wall paneling.

Fig. 7

Floor plan (ground floor) of the Guildhall in Exeter.

Source: The Building News and Engineering Journal / Apr. 23, 1875 / Denkel Archives.

The red circle shows the niche in the wall with the small rectangle that Shepherd's clock indicates. Before that, barely decipherable, the entry Clock.

Floor plan (ground floor) of the Guildhall in Exeter.

Source: The Building News and Engineering Journal / Apr. 23, 1875 / Denkel Archives.

The red circle shows the niche in the wall with the small rectangle that Shepherd's clock indicates. Before that, barely decipherable, the entry Clock.

Let's

come back to the issue of the foremen at Shepherd. William Robert

Sykes, who later

became known in railway signaling, is said to have worked for Shepherd

from around 1861 to 1863, for which, despite frequent mentioning in the

specialist

literature, no evidence can yet be found. A young man with

qualifications like Sykes could have easily been one of Shepherd's

foremen. In her last years, Shepherd Jr.’s daughter Mary Louisa

interestingly did not live far from Skyes in Herne Bay. Shepherd's

daughter and Lavinia Winifred Lightfoot (widow of a London jeweler) ran

a guesthouse there. Mary

Louisa died on June 26, 1927, at Kent & Canterbury Hospital and was

buried in Tankerton Cemetery.

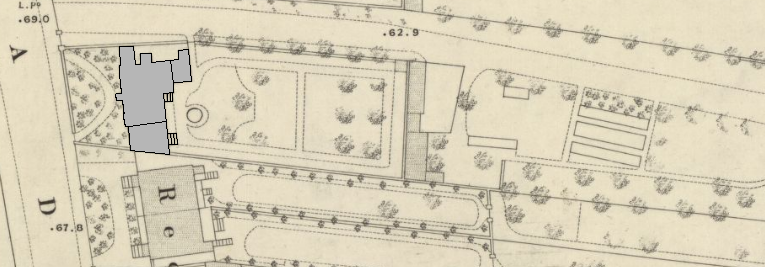

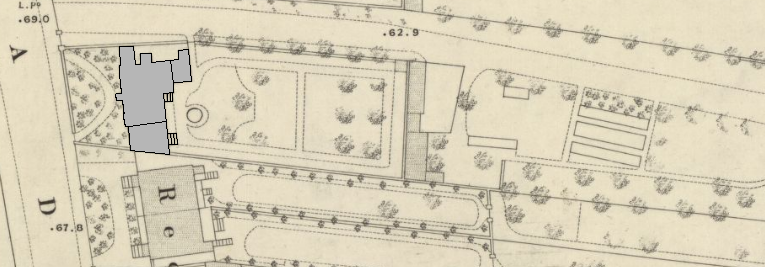

When

exactly the Shepherds family moved their private residence from

Leadenhall St to 38 Rectory Rd in Shacklewell remains unknown. In the

census of 1861, it is

recorded that the following people lived at this address: Charles

Shepherd Sr (Head), Mary Shepherd Sr (Wife),

the sons William Henry, George Augustus, and Francis John, as well as

the daughter of Charles Shepherd Jr Mary Louisa. The building at 38

Rectory Rd, also called

Rectory cottage, must have been a representative house. Old plans show

the floor plan of a large detached house with an ornamental front

garden, popular in Victorian times, and another deepened garden behind

the house. At that time, it could be found

in a rather rural setting, far from the noise and dirt of the

City of London. In old maps, the name Rectory villas can be found for

the few buildings in this street section (originally Shacklewell Lane /

New Road). Shepherd

Sr being able to afford such a residential property (purchase or rent?)

once more emphasize his economic success. Despite an intensive search,

no picture of the building has been found so far. Furthermore all

historical buildings on this side of the street unfortunately were

demolished after the war. Today some apartment blocks can be found at

the site. Nothing that remains shows a hint of the

noblesse that once characterized the area.

Charles Shepherd Sr died on June 21, 1865 at 38 Rectory Rd. The cause of death was reported as "softening of brain paralysis with apoplexy" - Shepherd was only 63 years old. In his will, dated July 24, 1865 (Draw up in February 1864), which is very short, he bequeathed everything to his wife Mary Shepherd including the Shepherd company. Mary Shepherd later was assumed embodying the function of a company owner, which can be concluded from the following documents: She called herself “manager” in the 1871 Census. In her will of March 1st, 1881, she expressly states that she was the owner of Shepherd & Son and that she ran the company together with her son William Henry. It is noteworthy that Charles Shepherd Sr did not consider his second eldest son William Henry in his will (Charles Shepherd Jr was still in India at the time). What could have been the reasons? At the time of his father's death, William Henry was 24 years old. Based on his age and his previous entitlement, he should have been more than able to continue running the company. In fact, given the times, it was more common to provide the widow of the company owner with some kind of pension or assets from the company ensuring her economic security. It was far less likely that a woman became the owner of the company. Mary Shepherd might have played an important role in the management even before the death of her husband. It appears that Mary Shepherd successfully sustained the company for 16 more years and also kept the family members in line. When she died on March 8, 1881, she bequeathed the company to her son William Henry. Only a short time later, the other son George Augustus (former chronometer maker) leaves the family residence in Rectory Rd, marries Esther Templer Spalding in December 1881, and moves into the house at 46 Shelgate Rd / Battersea. In the census of 1881, he is mentioned as a clerk in the public service. George Augustus Shepherd died from tuberculosis on Dec 18, 1886, at Bolingbroke Hospital Wakehurst Rd, Wandsworth Common, SW11 6HN, at the age of only 37. The death was reported by his brother Charles Shepherd Jr, residing at 2 Alexandra Rd.

The last address of George Augustus Shepherd was 26 Lindore Rd New Wandsworth. George Augustus had a son named Arthur Charles Shepherd, (born Sept. 18, 1883). The middle name Charles could be a reference to his uncle Charles Shepherd Jr (godfather?). Arthur Charles had four daughters, the last died in 2002. One cannot help but wonder if there are relatives from the Arthur Charles legacy who may own family documents and thus could answer some questions. On the search for people of the next generation, data protection, unfortunately, turned out to be an insurmountable hurdle for the moment. In fact it seems easier to reconstruct the life of a historical person who lived 200 years ago than to find a relative of Shepherd who is still alive today.

Arthur Charles Shepherd and his wife Esther Templar Shepherd (nee Spalding).

Arthur Charles may have been Charles Shepherd Jn's godchild.

Source: private collection

Shepherd / London

New Data to Family- and Company History

Part 2

Eugen Denkel

Translation from German by Svenja Viola Bungarten

In the second part of the article, we will briefly touch on Charles Shepherd Sr. before elaborating more details about his son Charles Jr.

The Shepherd company has not only supplied clock systems for English railway companies but their supply has also been documented for Spain. The "EL GUADALETTE" of July 7, 1856 reports on the electrical clock system in Jerez de la Frontera:

Shepherd is further credited in the article: „Pero el regulador que hemos descrito, y que es patente de su fabricante Shepherd….“ A part of this clock system is still preserved today. On the Placa del Arenal there is a clock with the inscription Losada on the four dials on a cast-iron lamppost. It originally housed a Shepherd electric slave clockwork controlled by a master clock in the Jerez de la Frontera train station. Due to a lack of maintenance, the clock failed and was replaced by a purely mechanical clockwork (today in the Museos de la Atalaya), made by José Rodríguez Losada / London. Part of the reason Shepherd supplied electrical clock systems to Spain was that the railways there were built by English engineers. The clock in Jerez de la Frontera shows great similarities with the clock made by A. Bain placed opposite of house No 448 Strand / London. Another clock of this type was located just outside the Telegraph Office on Castle St / Liverpool. The latter could be from Shepherd. Perhaps Shepherd acquired the molds for these "lantern clocks" from the bankruptcy estate of Bain, who had to file for bankruptcy in 1852. This type of clock had to be a special construction, a normal lantern head cannot be used, all four sides (dial faces) should be vertical and stand parallel to each other. Only this construction enables a relatively simple clock hand mechanism without additional cardan joints. In a lantern for lighting purposes, the discs are "tilted", the lantern body is wider at the top and narrower at the bottom so that the area directly under the lantern will not be shaded by the lantern body. Such a construction is not very suitable for a clock. The fact that Shepherd was in possession of molds for outdoor clocks is further documented by correspondence regarding St Johns / Exeter clock.

Reloj de Losada en la plaza del Arenal de Jerez de la Frontera (España)

Author: El Pantera, Licence: CC BY-SA 4.0 Source: Wikimedia Commons

On the Placa del Arenal there is a clock with the inscription Losada on the four dials on a cast-iron lamppost. It originally housed a Shepherd electric slave clockwork controlled by a master clock in the Jerez de la Frontera train station.

The Shepherd clocks / watches that are preserved to this day have different signatures on the dial. We find Charles Shepherd, Shepherd & Son, William Henry Shepherd, and among electric clocks Shepherd Patentee. The latter refers primarily to Shepherd Jr. Assuming that Shepherd's marine chronometers were numbered consecutively or chronologically, it can be determined that up to around 1865 they were signed by Charles Shepherd. After that the signature transformed into Shepherd & Son. This could correlate with the dates of Shepherd senior's life, or could lead to the conclusion that Shepherd & Son was established as the signature after his death in 1865. This is the time when his widow Mary became the proprietor. For chronometer No. 1723 we have a chronological assignment since it was submitted to the Greenwich chronometer test in 1867. It is signed: Shepherd & Son 53 Leadenhall St, London.

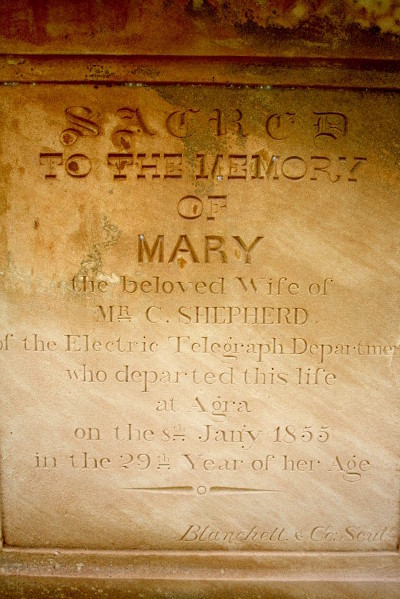

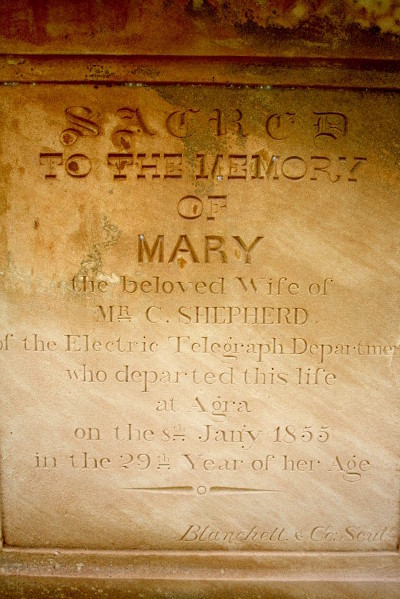

Let us now turn to Charles Shepherd Jr. In September 1853 he and his wife Mary reached Calcutta and from February 1854 on they lived in Hastings Street there. He moved into a three-story building, which was assigned to them as their residence. The building also housed the Electric Telegraph Office, a workshop, and an education room. Hastings St was later renamed Kiran Shankar Ray Rd. It was one of the “fine and prestigious” addresses in Calcutta, and the governor's residence was in the immediate vicinity. It could not be determined yet at which house number exactly Shepherd resided. However, we can find a hint to that matter in the files about the owner of that very building - Gohlam Mohammad.

In 1854 Shepherd was transferred to Agra. Shepherd held the position of Deputy Superintendent for Bengal with the Telegraph Administration, reporting directly to O'Shaughnessy. The same position was simultaneously occupied by I.R.L. Branton for Madras and Dr. H. Green for Bombay. Like Shepherd, Branton fell out of favor with O'Shaughnessy after a short time, Green resigned of his own accord. It seems that Shepherd occupied his position the longest until the death of his wife "pulled the ground from under his feet". For those more interested in the background of Shepherd's professional problems during his time in the telegraph administration, I highly recommend the article by Saroj Ghose: William O'Shaughnessy - an Innovator Entrepreneur, in Indian Journal of History of Science 29 / 1994. In this article, Saroj Ghose takes an in-depth look at the person O'Shaughnessy. The article reveals how difficult it must have been for O'Shaughnessy's staff to work under his leadership. Saroj Ghose writes that O'Shaughnessy may have asked too much of his staff:

Fig. 10

Inscription on Mary Shepherd's gravestone in Agra.

Photographer / Copyright: Gina Patczowsky

After retiring from the service of the telegraph administration, several leads point to C. Shepherd Jr. working as a photographer in Agra. In Mrs. RM Cooplan's book, A LADY'S ESCAPE FROM GWALIOR AND LIFE IN THE FORT OF AGRA DURING THE MUTINIES OF 1857, an unnamed photographer is mentioned, who, coming from Calcutta, took photographs at Gwalior. This must have been before the uprising spread to Gwalior in April 1857. Myriad European colonisers were defeated there on June 14th. Many survivors took refuge in the care of the local Maharaja and were then evacuated to Agra. Regarding the photographs Mrs. Coopland writes: "A little before this, a man from Calcutta arrived to take photographs, and stayed some time. Some of these photographs were recovered after the mutinies, and sent into Agra". It is noteworthy that photographs were found in Gwalior after the uprisings and were then sent to Agra. Who could have been the addressee for these photographs? Could it be of interest to the people who had been portrayed and were now residing in Agra? Were photographs intended to be returned to their original owners, or were they sent to a local photographer? If the addressee was a photographer (possibly the one mentioned in Gwalior), it is reasonable to assume that it could be Charles Shepherd. He is indeed mentioned in the "Agra Fort Directory according to the Census taken on the 27th July 1857 by Asst Surgeon JP Walker MD", he can be found listed as a photographic artist. Shepherd was billeted in the same section of the fort (Armory Square west side) along with his later brother-in-law Henry Marshall (chemist at Hulse & Nephew). No other photographer in Agra is mentioned for the time (1857).

In March an exhibition is known to be held by the Photographic Society of Bengal in Calcutta, where photographers could present their pictures to a larger audience and thus increase their chances of commercial success. Photographers would find themselves able to purchase everything they needed to do their job here. Furthermore, the latest developments on the European market were on display on the markets in Calcutta quite immediatley after their release. Thus, a trip was worthwhile, despite the hardships for a photographer from Agra. From Shepherd's perspective, it might have made sense to bring his daughter to Calcutta at this time. Perhaps he sensed the catastrophe the country was heading for and brought her to safety. In June 1857 the siege of Agra Fort, in which 6,000 Europeans were entrenched, began. Military units were deployed to defend the fort, and Shepherd served in an infantry unit. We can find documents that list his name in the Agra Fort Directory and the subsequent reward with the "Indian Mutiny Medal". (I owe the reference about Shepherd's medal award to a London gentleman). The Europeans' quarters and businesses in Agra were pillaged during the siege. Shepherd's photo studio in Agra is also likely to have fallen victim to this arson.

Today we only know of photographs by him from the time after the uprising. Charles Shepherd Jr. married Sophia Marshall in Agra on March 21, 1863. The third child of Francis and Jane Marshall, she was born in 1829 in Easenhall / Warwickshire. Sophia Marshall is listed in the 1861 census (England) with her sister Eliza. She can therefore only have traveled to India after this date. The history of the Marshall family repeatedly shows references to Shepherd, especially later in England. This data is of special interest because Sophia Shepherd, as heir to Charles Shepherd Jr. later named her sisters Caroline and Lucy Marshall as beneficiaries in her will. Caroline Marshall survived her sister Lucy and her estate passed to her niece Olive Marshall in her will. There is an Olive Marshall who emigrated to New Zealand in 1925 and died there in 1961. She could be identical to Sophia Shepherd's niece. With knowledge of the above inheritance, it is possible to find relatives who are still alive today and thus perhaps to close significant gaps in the family history. Her aunt Caroline Marshall, Sophia Shepherd's sister, writes about Olive Marshall in her will, referring to the tragic events in her brother Henry's family: "...I bequeath the same absolutely to my dear nice Olive Marshall only child of my deceased youngest brother Henry Marshall late of Agra East Indies...“ All other children of Henry had already died in India.

Charles Shepherd Jr. was very successful in India both as a photographer and a printer. Especially the partnership with Samuel Bourne proved fruitful regarding entrepreneurship and artistical quality. However, there must have been important reasons that caused him to return to England. The reasons for this are as yet unknown. According to the data available and evaluated so far, it is most likely that Charles Shepherd Jr. and his wife Sophia left Bombay for Brindisi with the "SS Bangalore" in November 1877. Several entries in contemporary sources can prove the above. We furthermore have good reason to believe that they occupied the house at 2 Alexandra Rd St John's Wood (London) quite promptly after their return. The residence can be described as a detached three-story building, one of the so-called middle-class villas. The 1881 census shows that the Shepherds employed two domestic servants. Alexandra Rd is located in the district of St. John's Wood in northwest London, in the immediate vicinity of South Hampstead train station. So far only two historic photographs are showing the backside of the building. No 2 is the only house in this street area that was demolished after the war, the historic buildings in close proximity remained intact. Therefore, conclusions about the appearance of No 2 are possible as the designs mostly followed a unified style at the time. Charles Shepherd must have returned from India with assets that enabled him to rent this prestigious home, hire domestic staff, and start a new business in the field of electric clocks. In particular, his new patents, the construction, and the testing of prototypes may have required the use of appropriate funds. Shepherd resided at 2 Alexandra Rd from ca. 1877 to ca. 1887. The address is also found in his patents Nos. 2467/(1878), 6790/(1878), US 222,424/(1879), 3696/(1881), 5308 / (1885), as well as in a letter to Airy in 1881 and a further letter to the Greenwich Observatory in 1887.

According to the 1891 census we find Shepherd Jr. and his wife residing far from London in Falmouth / Florence Place in Cornwall at the time. Nonetheless they appear to have lived in Falmouth only briefly, as neither of them is listed in the directories of the following years. In 1895 the Shepherds resided at 40 Eastbourne Terrace / Paddington - we can therefore conclude that Shepherd returned to London, even though the reasons for the move remain unknown.

The new residence at 40 Eastbourne Terrace is only documented in the 1895 will of Caroline Marshall (sister of Shepherd's wife Sophia) so far; it lists Charles Shepherd and his wife Sophia Shepherd as witnesses. "... Witnesses CHARLES SHEPHERD 40 Eastbourne Terrace Paddington - . SOPHIA SHEPHERD both of same address". We find the entry Woodhouse Mrs. M. Apartments in the 1895 Directory, at 40 Eastbourne Terrace. According to this data, Shepherd may have merely rented an apartment there instead of a complete house like in Alexandra Rd.

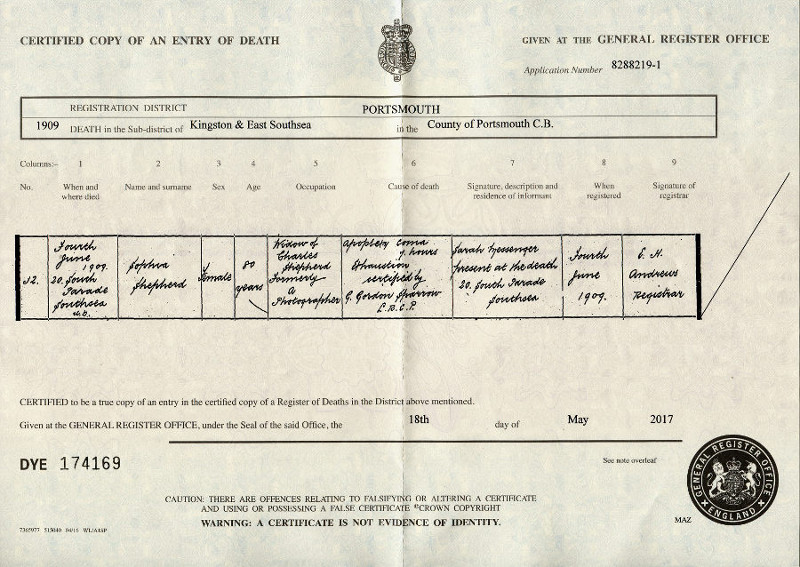

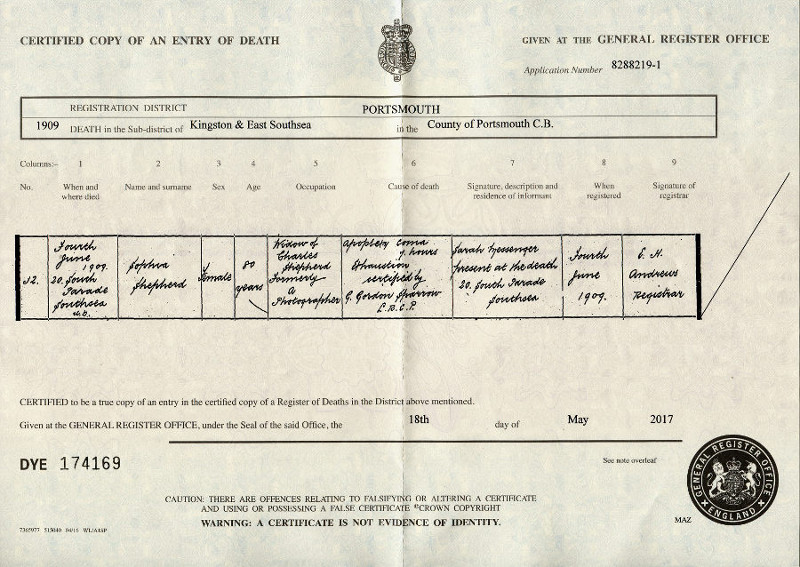

Since 1901 Shepherd seems to have been located in Southsea near Portsmouth. First at 14 South Parade and then at 20 South Parade. Both prestigious addresses directly on a large park with a sea view. The buildings still exist today. Shepherd seems to have spent the last years of his life there until he died on July 1, 1905, at 20 South Parade / Southsea. The registration document relating to his death also makes reference to his employment with the Telegraph Administration in India. Under heading 3, occupation, the following is noted: "Formerly an Electrician (Indian Telegraph)". Shepherd is referred to as: "Electrical Engineer, retired", in the 1901 Census, a statement which he may have made to the Census investigators.

It is interesting that Charles Shepherd, never referred to himself as a "photographer" in the documents available so far. The well-known British photo historian Hugh Ashley Rayner writes in his book: "Photographic Journeys in the Himalayas" that according to Samuel Bourne (business partner of Shepherd in India):

Apparently, once in England, Shepherd avoided referring to his work as a photographer in India. It was only after his death that his former work as a photographer was mentioned by third parties. Interestingly, the death certificate of his second wife Sophia dated June 4, 1909, states that she is the widow of Charles Shepherd a former Photographer. The death of Charles Shepherd Jr. was ascertained by Dr. G. Gordon Sparrow of Southsea, who also attested the death of Sophia Shepherd in 1909. Charles' cause of death is listed as "pericardium" and "exhaustion," also noting that Shepherd suffered from a heart condition through out a year. As Dr. Gordon Sparrow is on both Charles' and his wife's death certificates, and details like the former werde noted, we can assume that Dr. Gordon Sparrow was the Shepherds' "family doctor". In that capacity, Dr. Gordon Sparrow could have known quite a bit of the social and private life of the Shepherds. The Shepherds may have mentioned their time and occupation in India. It may have been he who caused the notation "photographer" on Sophia Shepherd's death certificate and provided us the long-sought proof of the identity of Shepherd the engineer/chronometer maker and Shepherd the photographer in India. The Death Certificate contains important information regarding another person who was present at his deathbed. Here his niece Jane Lucy Marshall is mentioned, as well as her address listed as 2 Marmion Avenue Southsea. She lived in close proximity to her aunt or uncle. This can be interpreted as a further proof of Shepherd's close ties to the Marshall family.

Fig. 11

Death certificate of Sophia Shepherd, widow of Charles Shepherd Jn.

It bears the notice: "Widow of Charles Shepherd formerly a photographer".

Copyright: Crown Copyright

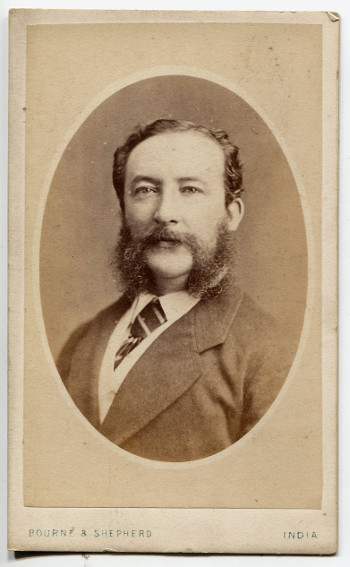

Astonishingly, only very few illustrations with direct reference to the Shepherd family are known. Just a few portraits probably show Shepherd Jr., e.g. a portrait now in the collections of the V&A Museum, valentine cards in a private collection, and a CDV from 1873 which is also held in a private collection. The photograph in the Victoria and Albert Museum originally belonged to the collection of the Royal Photographic Society, which, however, transferred parts of its collection to the V&A. Nevertheless the lack of consistency should lead to doubts about the dating to 1865. The photograph shows an elderly man. However, Shepherd Jr was only 36 years old. The picture must have been taken later than 1865. Also, the author has not yet been able to determine the reason on which the certainty of Charles Sheperd Jr's identity is based on. If the dating is correct and there are no direct references to Shepherd Jr to be found it would prove worthy to pursue whether it could not have been Shepherd Sn. who was pictured. 1865 was the year of his death. However, the person depicted on Valentine's cards bears a close resemblance to the person portrayed on the 1873 CDV from Bombay, and it can be said with some certainty that this could portray Shepherd Jr.

If you look back at the history of the Shepherd & Son company today, it seems to have vanished into thin air around 1900. By 1881/82 Shepherd must have moved their business from Leadenhall St to Talbot Court and by 1888 there is only William Henry Shepherd on Railway Place, just opposite to Fenchurch St (Blackwall) railway station. Charles Shepherd Jr. left London at this time, as did his daughter. George Augustus Shepherd had previously given up his activity as a chronometer maker and watches with the signature of the Shepherd Railway place cannot be found except for a single chronometer. What led to this quiet end of the Shepherd company? Could it have something to do with disagreements in the family, was it economic reasons, or are the reasons to be found in the person of the last company owner, William Henry Shepherd, who was always somewhat overshadowed by his famous family members? Unfortunately, there is not enough clear and reliable data to be able to make a well-founded statement here.

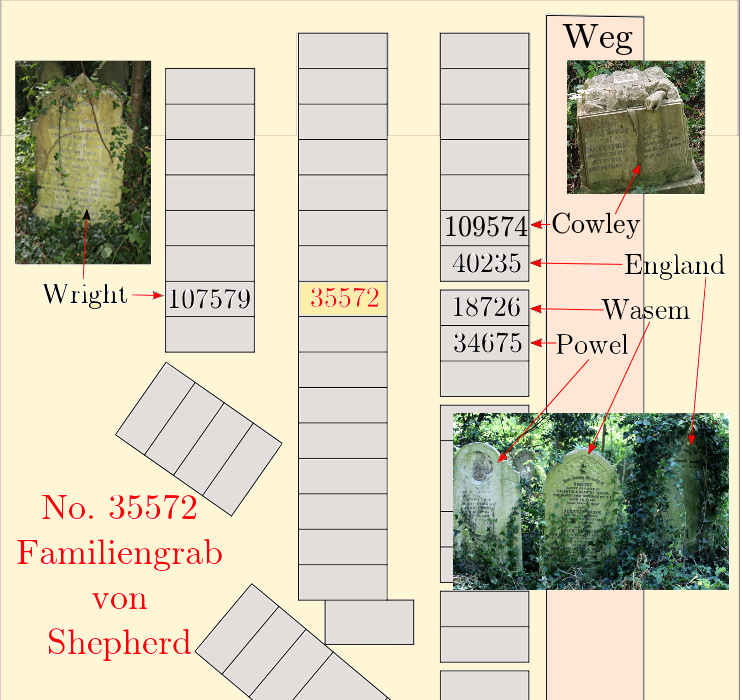

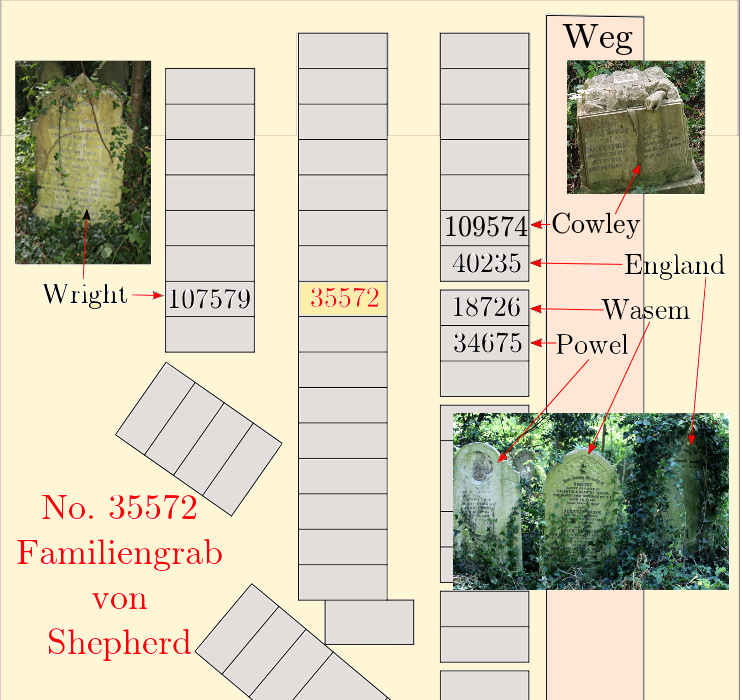

Finally, some information about Charles Shepherd Sr.'s final resting place. His wife Mary and son Francis John are buried in Abney Park Cemetery. According to the Abney Park Trust, all three people are buried in grave no. 035572 F07. The tombstone of the family grave has disappeared, and strangely enough, there is no grave border. What led to the complete removal of all traces of the burial site is unclear. The exact spot can only be localized based on existing tombstones from other graves in the immediate vicinity and a site plan. The hope remains that a small memorial stone will be erected in the future to remind us that family members of an important English clock and watchmaking family are buried here. According to information from the responsible organizations, such a project is feasible.

Here is what the Royal Observatory Greenwich has to say about Shepherd's master clock in the observatory on its website:

Shepherd's precision electric pendulum clock was the defining time clock in the United Kingdom and beyond for almost 70 years. They made it possible for the observatory to introduce a time service based on electrical impulses for the first time in 1853, which played a key role in Greenwich Mean Time becoming established in the United Kingdom. They were taken out of service almost at the same time as the Shepherd company went out of business. Some other observatories still have Shepherd precision pendulum clocks, e.g. Neuchatel and Melbourne, while others can only be verified based on documents, such as Madras and Bombay. The history of the clock in Neuchatel, which was the master clock for the time service of the observatory and in parts of Switzerland from 1859 to 1901, is particularly well documented. The depiction of the clock and its dial on diplomas that were awarded as part of chronometer tests shows the importance of the clock for the observatory and thus also its appreciation. The clock was recently restored/conserved and documented in an exemplary manner.

In conclusion, a lot of new data has been found, which held diverse surprises, especially the identicality of C. Shepherd Jr. and photographer Shepherd in India. However, many new gaps in knowledge were also clearly identified. Thus, Shepherd's story remains far from complete. There is still a great deal of work left for future clock historians.

The German version of the above article first published in

Chronometrie, Mitteilungen der Deutsche Gesellschaft für

Chronometrie 2019 Nr. 158 S. 24–29 / Nr. 159 S. 24-30

Fig. 8

38 Rectory Road / Residence of the Shepherd family.

Source (extract): London - Middlesex III.97

Surveyed: 1868, Published: 1872. Licence: Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland (CC-BY)

38 Rectory Road / Residence of the Shepherd family.

Source (extract): London - Middlesex III.97

Surveyed: 1868, Published: 1872. Licence: Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland (CC-BY)

Charles Shepherd Sr died on June 21, 1865 at 38 Rectory Rd. The cause of death was reported as "softening of brain paralysis with apoplexy" - Shepherd was only 63 years old. In his will, dated July 24, 1865 (Draw up in February 1864), which is very short, he bequeathed everything to his wife Mary Shepherd including the Shepherd company. Mary Shepherd later was assumed embodying the function of a company owner, which can be concluded from the following documents: She called herself “manager” in the 1871 Census. In her will of March 1st, 1881, she expressly states that she was the owner of Shepherd & Son and that she ran the company together with her son William Henry. It is noteworthy that Charles Shepherd Sr did not consider his second eldest son William Henry in his will (Charles Shepherd Jr was still in India at the time). What could have been the reasons? At the time of his father's death, William Henry was 24 years old. Based on his age and his previous entitlement, he should have been more than able to continue running the company. In fact, given the times, it was more common to provide the widow of the company owner with some kind of pension or assets from the company ensuring her economic security. It was far less likely that a woman became the owner of the company. Mary Shepherd might have played an important role in the management even before the death of her husband. It appears that Mary Shepherd successfully sustained the company for 16 more years and also kept the family members in line. When she died on March 8, 1881, she bequeathed the company to her son William Henry. Only a short time later, the other son George Augustus (former chronometer maker) leaves the family residence in Rectory Rd, marries Esther Templer Spalding in December 1881, and moves into the house at 46 Shelgate Rd / Battersea. In the census of 1881, he is mentioned as a clerk in the public service. George Augustus Shepherd died from tuberculosis on Dec 18, 1886, at Bolingbroke Hospital Wakehurst Rd, Wandsworth Common, SW11 6HN, at the age of only 37. The death was reported by his brother Charles Shepherd Jr, residing at 2 Alexandra Rd.

Fig. 9

Lindore Road No 26 / Last residence of George Augustus Shepherd.

© 2019 Denkel

Lindore Road No 26 / Last residence of George Augustus Shepherd.

© 2019 Denkel

The last address of George Augustus Shepherd was 26 Lindore Rd New Wandsworth. George Augustus had a son named Arthur Charles Shepherd, (born Sept. 18, 1883). The middle name Charles could be a reference to his uncle Charles Shepherd Jr (godfather?). Arthur Charles had four daughters, the last died in 2002. One cannot help but wonder if there are relatives from the Arthur Charles legacy who may own family documents and thus could answer some questions. On the search for people of the next generation, data protection, unfortunately, turned out to be an insurmountable hurdle for the moment. In fact it seems easier to reconstruct the life of a historical person who lived 200 years ago than to find a relative of Shepherd who is still alive today.

Arthur Charles Shepherd and his wife Esther Templar Shepherd (nee Spalding).

Arthur Charles may have been Charles Shepherd Jn's godchild.

Source: private collection

Shepherd / London

New Data to Family- and Company History

Part 2

Eugen Denkel

Translation from German by Svenja Viola Bungarten

In the second part of the article, we will briefly touch on Charles Shepherd Sr. before elaborating more details about his son Charles Jr.

The Shepherd company has not only supplied clock systems for English railway companies but their supply has also been documented for Spain. The "EL GUADALETTE" of July 7, 1856 reports on the electrical clock system in Jerez de la Frontera:

| „RELOJ ELECTRICO: Hace algunos

dias que dimos cuenta a nuestros

lectores de la nueva mejora, que la direccion del ferro-carril ha

establecido en le estacion de nuestro pueblo, colocando an ella un

magnifico reloj electrico, que por su belleza,..“. "ELECTRIC CLOCK: A few days ago we told our readers about the new improvement that the railroad management has made in our city's train station by installing a magnificent electric clock...". |

Shepherd is further credited in the article: „Pero el regulador que hemos descrito, y que es patente de su fabricante Shepherd….“ A part of this clock system is still preserved today. On the Placa del Arenal there is a clock with the inscription Losada on the four dials on a cast-iron lamppost. It originally housed a Shepherd electric slave clockwork controlled by a master clock in the Jerez de la Frontera train station. Due to a lack of maintenance, the clock failed and was replaced by a purely mechanical clockwork (today in the Museos de la Atalaya), made by José Rodríguez Losada / London. Part of the reason Shepherd supplied electrical clock systems to Spain was that the railways there were built by English engineers. The clock in Jerez de la Frontera shows great similarities with the clock made by A. Bain placed opposite of house No 448 Strand / London. Another clock of this type was located just outside the Telegraph Office on Castle St / Liverpool. The latter could be from Shepherd. Perhaps Shepherd acquired the molds for these "lantern clocks" from the bankruptcy estate of Bain, who had to file for bankruptcy in 1852. This type of clock had to be a special construction, a normal lantern head cannot be used, all four sides (dial faces) should be vertical and stand parallel to each other. Only this construction enables a relatively simple clock hand mechanism without additional cardan joints. In a lantern for lighting purposes, the discs are "tilted", the lantern body is wider at the top and narrower at the bottom so that the area directly under the lantern will not be shaded by the lantern body. Such a construction is not very suitable for a clock. The fact that Shepherd was in possession of molds for outdoor clocks is further documented by correspondence regarding St Johns / Exeter clock.

Reloj de Losada en la plaza del Arenal de Jerez de la Frontera (España)

Author: El Pantera, Licence: CC BY-SA 4.0 Source: Wikimedia Commons

On the Placa del Arenal there is a clock with the inscription Losada on the four dials on a cast-iron lamppost. It originally housed a Shepherd electric slave clockwork controlled by a master clock in the Jerez de la Frontera train station.

The Shepherd clocks / watches that are preserved to this day have different signatures on the dial. We find Charles Shepherd, Shepherd & Son, William Henry Shepherd, and among electric clocks Shepherd Patentee. The latter refers primarily to Shepherd Jr. Assuming that Shepherd's marine chronometers were numbered consecutively or chronologically, it can be determined that up to around 1865 they were signed by Charles Shepherd. After that the signature transformed into Shepherd & Son. This could correlate with the dates of Shepherd senior's life, or could lead to the conclusion that Shepherd & Son was established as the signature after his death in 1865. This is the time when his widow Mary became the proprietor. For chronometer No. 1723 we have a chronological assignment since it was submitted to the Greenwich chronometer test in 1867. It is signed: Shepherd & Son 53 Leadenhall St, London.

Let us now turn to Charles Shepherd Jr. In September 1853 he and his wife Mary reached Calcutta and from February 1854 on they lived in Hastings Street there. He moved into a three-story building, which was assigned to them as their residence. The building also housed the Electric Telegraph Office, a workshop, and an education room. Hastings St was later renamed Kiran Shankar Ray Rd. It was one of the “fine and prestigious” addresses in Calcutta, and the governor's residence was in the immediate vicinity. It could not be determined yet at which house number exactly Shepherd resided. However, we can find a hint to that matter in the files about the owner of that very building - Gohlam Mohammad.

In 1854 Shepherd was transferred to Agra. Shepherd held the position of Deputy Superintendent for Bengal with the Telegraph Administration, reporting directly to O'Shaughnessy. The same position was simultaneously occupied by I.R.L. Branton for Madras and Dr. H. Green for Bombay. Like Shepherd, Branton fell out of favor with O'Shaughnessy after a short time, Green resigned of his own accord. It seems that Shepherd occupied his position the longest until the death of his wife "pulled the ground from under his feet". For those more interested in the background of Shepherd's professional problems during his time in the telegraph administration, I highly recommend the article by Saroj Ghose: William O'Shaughnessy - an Innovator Entrepreneur, in Indian Journal of History of Science 29 / 1994. In this article, Saroj Ghose takes an in-depth look at the person O'Shaughnessy. The article reveals how difficult it must have been for O'Shaughnessy's staff to work under his leadership. Saroj Ghose writes that O'Shaughnessy may have asked too much of his staff:

|

"...there are

indications that he probably demanded too much from his

subordinates…..He wanted a similar degree of zeal and activity from all

his subordinates, particularly from his deputies, Green, Bruton, and

Shepherd and recommended their dismissal.“

Saroj Ghose further writes regarding O'Shaughnessy: "...Soon he fell victim to cerebral

congestion and even on recovery, continued to suffer from nervous

excitement.“

|

Fig. 10

Inscription on Mary Shepherd's gravestone in Agra.

Photographer / Copyright: Gina Patczowsky

After retiring from the service of the telegraph administration, several leads point to C. Shepherd Jr. working as a photographer in Agra. In Mrs. RM Cooplan's book, A LADY'S ESCAPE FROM GWALIOR AND LIFE IN THE FORT OF AGRA DURING THE MUTINIES OF 1857, an unnamed photographer is mentioned, who, coming from Calcutta, took photographs at Gwalior. This must have been before the uprising spread to Gwalior in April 1857. Myriad European colonisers were defeated there on June 14th. Many survivors took refuge in the care of the local Maharaja and were then evacuated to Agra. Regarding the photographs Mrs. Coopland writes: "A little before this, a man from Calcutta arrived to take photographs, and stayed some time. Some of these photographs were recovered after the mutinies, and sent into Agra". It is noteworthy that photographs were found in Gwalior after the uprisings and were then sent to Agra. Who could have been the addressee for these photographs? Could it be of interest to the people who had been portrayed and were now residing in Agra? Were photographs intended to be returned to their original owners, or were they sent to a local photographer? If the addressee was a photographer (possibly the one mentioned in Gwalior), it is reasonable to assume that it could be Charles Shepherd. He is indeed mentioned in the "Agra Fort Directory according to the Census taken on the 27th July 1857 by Asst Surgeon JP Walker MD", he can be found listed as a photographic artist. Shepherd was billeted in the same section of the fort (Armory Square west side) along with his later brother-in-law Henry Marshall (chemist at Hulse & Nephew). No other photographer in Agra is mentioned for the time (1857).

In March an exhibition is known to be held by the Photographic Society of Bengal in Calcutta, where photographers could present their pictures to a larger audience and thus increase their chances of commercial success. Photographers would find themselves able to purchase everything they needed to do their job here. Furthermore, the latest developments on the European market were on display on the markets in Calcutta quite immediatley after their release. Thus, a trip was worthwhile, despite the hardships for a photographer from Agra. From Shepherd's perspective, it might have made sense to bring his daughter to Calcutta at this time. Perhaps he sensed the catastrophe the country was heading for and brought her to safety. In June 1857 the siege of Agra Fort, in which 6,000 Europeans were entrenched, began. Military units were deployed to defend the fort, and Shepherd served in an infantry unit. We can find documents that list his name in the Agra Fort Directory and the subsequent reward with the "Indian Mutiny Medal". (I owe the reference about Shepherd's medal award to a London gentleman). The Europeans' quarters and businesses in Agra were pillaged during the siege. Shepherd's photo studio in Agra is also likely to have fallen victim to this arson.

Today we only know of photographs by him from the time after the uprising. Charles Shepherd Jr. married Sophia Marshall in Agra on March 21, 1863. The third child of Francis and Jane Marshall, she was born in 1829 in Easenhall / Warwickshire. Sophia Marshall is listed in the 1861 census (England) with her sister Eliza. She can therefore only have traveled to India after this date. The history of the Marshall family repeatedly shows references to Shepherd, especially later in England. This data is of special interest because Sophia Shepherd, as heir to Charles Shepherd Jr. later named her sisters Caroline and Lucy Marshall as beneficiaries in her will. Caroline Marshall survived her sister Lucy and her estate passed to her niece Olive Marshall in her will. There is an Olive Marshall who emigrated to New Zealand in 1925 and died there in 1961. She could be identical to Sophia Shepherd's niece. With knowledge of the above inheritance, it is possible to find relatives who are still alive today and thus perhaps to close significant gaps in the family history. Her aunt Caroline Marshall, Sophia Shepherd's sister, writes about Olive Marshall in her will, referring to the tragic events in her brother Henry's family: "...I bequeath the same absolutely to my dear nice Olive Marshall only child of my deceased youngest brother Henry Marshall late of Agra East Indies...“ All other children of Henry had already died in India.

Charles Shepherd Jr. was very successful in India both as a photographer and a printer. Especially the partnership with Samuel Bourne proved fruitful regarding entrepreneurship and artistical quality. However, there must have been important reasons that caused him to return to England. The reasons for this are as yet unknown. According to the data available and evaluated so far, it is most likely that Charles Shepherd Jr. and his wife Sophia left Bombay for Brindisi with the "SS Bangalore" in November 1877. Several entries in contemporary sources can prove the above. We furthermore have good reason to believe that they occupied the house at 2 Alexandra Rd St John's Wood (London) quite promptly after their return. The residence can be described as a detached three-story building, one of the so-called middle-class villas. The 1881 census shows that the Shepherds employed two domestic servants. Alexandra Rd is located in the district of St. John's Wood in northwest London, in the immediate vicinity of South Hampstead train station. So far only two historic photographs are showing the backside of the building. No 2 is the only house in this street area that was demolished after the war, the historic buildings in close proximity remained intact. Therefore, conclusions about the appearance of No 2 are possible as the designs mostly followed a unified style at the time. Charles Shepherd must have returned from India with assets that enabled him to rent this prestigious home, hire domestic staff, and start a new business in the field of electric clocks. In particular, his new patents, the construction, and the testing of prototypes may have required the use of appropriate funds. Shepherd resided at 2 Alexandra Rd from ca. 1877 to ca. 1887. The address is also found in his patents Nos. 2467/(1878), 6790/(1878), US 222,424/(1879), 3696/(1881), 5308 / (1885), as well as in a letter to Airy in 1881 and a further letter to the Greenwich Observatory in 1887.

According to the 1891 census we find Shepherd Jr. and his wife residing far from London in Falmouth / Florence Place in Cornwall at the time. Nonetheless they appear to have lived in Falmouth only briefly, as neither of them is listed in the directories of the following years. In 1895 the Shepherds resided at 40 Eastbourne Terrace / Paddington - we can therefore conclude that Shepherd returned to London, even though the reasons for the move remain unknown.

The new residence at 40 Eastbourne Terrace is only documented in the 1895 will of Caroline Marshall (sister of Shepherd's wife Sophia) so far; it lists Charles Shepherd and his wife Sophia Shepherd as witnesses. "... Witnesses CHARLES SHEPHERD 40 Eastbourne Terrace Paddington - . SOPHIA SHEPHERD both of same address". We find the entry Woodhouse Mrs. M. Apartments in the 1895 Directory, at 40 Eastbourne Terrace. According to this data, Shepherd may have merely rented an apartment there instead of a complete house like in Alexandra Rd.

Since 1901 Shepherd seems to have been located in Southsea near Portsmouth. First at 14 South Parade and then at 20 South Parade. Both prestigious addresses directly on a large park with a sea view. The buildings still exist today. Shepherd seems to have spent the last years of his life there until he died on July 1, 1905, at 20 South Parade / Southsea. The registration document relating to his death also makes reference to his employment with the Telegraph Administration in India. Under heading 3, occupation, the following is noted: "Formerly an Electrician (Indian Telegraph)". Shepherd is referred to as: "Electrical Engineer, retired", in the 1901 Census, a statement which he may have made to the Census investigators.

It is interesting that Charles Shepherd, never referred to himself as a "photographer" in the documents available so far. The well-known British photo historian Hugh Ashley Rayner writes in his book: "Photographic Journeys in the Himalayas" that according to Samuel Bourne (business partner of Shepherd in India):

| “In later life, he became somewhat reticent about his earlier career as a commercial photographer in India. In later Victorian and Edwardian England, being a professional photographer had very little social status attached to it, and a successful businessman and Justice of the Peace would probably not wish it be widely known that he had once been actively involved in anything so socially demeaning as running a Portrait studio!” |

Apparently, once in England, Shepherd avoided referring to his work as a photographer in India. It was only after his death that his former work as a photographer was mentioned by third parties. Interestingly, the death certificate of his second wife Sophia dated June 4, 1909, states that she is the widow of Charles Shepherd a former Photographer. The death of Charles Shepherd Jr. was ascertained by Dr. G. Gordon Sparrow of Southsea, who also attested the death of Sophia Shepherd in 1909. Charles' cause of death is listed as "pericardium" and "exhaustion," also noting that Shepherd suffered from a heart condition through out a year. As Dr. Gordon Sparrow is on both Charles' and his wife's death certificates, and details like the former werde noted, we can assume that Dr. Gordon Sparrow was the Shepherds' "family doctor". In that capacity, Dr. Gordon Sparrow could have known quite a bit of the social and private life of the Shepherds. The Shepherds may have mentioned their time and occupation in India. It may have been he who caused the notation "photographer" on Sophia Shepherd's death certificate and provided us the long-sought proof of the identity of Shepherd the engineer/chronometer maker and Shepherd the photographer in India. The Death Certificate contains important information regarding another person who was present at his deathbed. Here his niece Jane Lucy Marshall is mentioned, as well as her address listed as 2 Marmion Avenue Southsea. She lived in close proximity to her aunt or uncle. This can be interpreted as a further proof of Shepherd's close ties to the Marshall family.

Fig. 11

Death certificate of Sophia Shepherd, widow of Charles Shepherd Jn.

It bears the notice: "Widow of Charles Shepherd formerly a photographer".

Copyright: Crown Copyright

Astonishingly, only very few illustrations with direct reference to the Shepherd family are known. Just a few portraits probably show Shepherd Jr., e.g. a portrait now in the collections of the V&A Museum, valentine cards in a private collection, and a CDV from 1873 which is also held in a private collection. The photograph in the Victoria and Albert Museum originally belonged to the collection of the Royal Photographic Society, which, however, transferred parts of its collection to the V&A. Nevertheless the lack of consistency should lead to doubts about the dating to 1865. The photograph shows an elderly man. However, Shepherd Jr was only 36 years old. The picture must have been taken later than 1865. Also, the author has not yet been able to determine the reason on which the certainty of Charles Sheperd Jr's identity is based on. If the dating is correct and there are no direct references to Shepherd Jr to be found it would prove worthy to pursue whether it could not have been Shepherd Sn. who was pictured. 1865 was the year of his death. However, the person depicted on Valentine's cards bears a close resemblance to the person portrayed on the 1873 CDV from Bombay, and it can be said with some certainty that this could portray Shepherd Jr.

|

|

| CDV probably showing C. Shepherd Jr. |

Reverse of CDV dated 1873 |

Fig. 12

The portrait above bears close resemblance to 1874 valentine cards clearly depicting Charles Shepherd Jn.

Copyright: Private collection.

The portrait above bears close resemblance to 1874 valentine cards clearly depicting Charles Shepherd Jn.

Copyright: Private collection.

If you look back at the history of the Shepherd & Son company today, it seems to have vanished into thin air around 1900. By 1881/82 Shepherd must have moved their business from Leadenhall St to Talbot Court and by 1888 there is only William Henry Shepherd on Railway Place, just opposite to Fenchurch St (Blackwall) railway station. Charles Shepherd Jr. left London at this time, as did his daughter. George Augustus Shepherd had previously given up his activity as a chronometer maker and watches with the signature of the Shepherd Railway place cannot be found except for a single chronometer. What led to this quiet end of the Shepherd company? Could it have something to do with disagreements in the family, was it economic reasons, or are the reasons to be found in the person of the last company owner, William Henry Shepherd, who was always somewhat overshadowed by his famous family members? Unfortunately, there is not enough clear and reliable data to be able to make a well-founded statement here.

Finally, some information about Charles Shepherd Sr.'s final resting place. His wife Mary and son Francis John are buried in Abney Park Cemetery. According to the Abney Park Trust, all three people are buried in grave no. 035572 F07. The tombstone of the family grave has disappeared, and strangely enough, there is no grave border. What led to the complete removal of all traces of the burial site is unclear. The exact spot can only be localized based on existing tombstones from other graves in the immediate vicinity and a site plan. The hope remains that a small memorial stone will be erected in the future to remind us that family members of an important English clock and watchmaking family are buried here. According to information from the responsible organizations, such a project is feasible.

Fig. 13

Location of the Shepherd Family grave at Abney Park London.

© Archiv Denkel

Location of the Shepherd Family grave at Abney Park London.

© Archiv Denkel

What, then, is Shepherd's

importance in the history of clockmaking?

Here is what the Royal Observatory Greenwich has to say about Shepherd's master clock in the observatory on its website:

| “In terms of the distribution of accurate time into everyday life, this is one of the most important clocks ever made.“ |

Shepherd's precision electric pendulum clock was the defining time clock in the United Kingdom and beyond for almost 70 years. They made it possible for the observatory to introduce a time service based on electrical impulses for the first time in 1853, which played a key role in Greenwich Mean Time becoming established in the United Kingdom. They were taken out of service almost at the same time as the Shepherd company went out of business. Some other observatories still have Shepherd precision pendulum clocks, e.g. Neuchatel and Melbourne, while others can only be verified based on documents, such as Madras and Bombay. The history of the clock in Neuchatel, which was the master clock for the time service of the observatory and in parts of Switzerland from 1859 to 1901, is particularly well documented. The depiction of the clock and its dial on diplomas that were awarded as part of chronometer tests shows the importance of the clock for the observatory and thus also its appreciation. The clock was recently restored/conserved and documented in an exemplary manner.

In conclusion, a lot of new data has been found, which held diverse surprises, especially the identicality of C. Shepherd Jr. and photographer Shepherd in India. However, many new gaps in knowledge were also clearly identified. Thus, Shepherd's story remains far from complete. There is still a great deal of work left for future clock historians.

Die deutsche Fassung des obigen Artikels erschien erstmals in Chronometrie, Mitteilungen der Deutsche Gesellschaft für Chronometrie 2019 Nr. 158 S. 24–29 / Nr. 159 S. 24-30

Back to article index...

Ian D. Fowler

Am Krängel 21, 51598 Friesenhagen

Germany

Tel. +49 (0) 2734 7559

Mobil 0171 9577910

e-mail Ian.Fowler@Historische-Zeitmesser.de

Am Krängel 21, 51598 Friesenhagen

Germany

Tel. +49 (0) 2734 7559

Mobil 0171 9577910

e-mail Ian.Fowler@Historische-Zeitmesser.de

Aktualisierungen 28.03.2023 / 26.03.2023 / 05.08.2022 /

06.02.2022 /

01.05.2021 /

26.02.2021